It cannot be be overlooked when regulating the sustainable natural resources (oil, gas and minerals) sector that such resources are finite. The benefits of the extracted sustainable natural resources, usually measured narrowly in financial terms, has diminishing returns once the resource arrives at its final destination. Meanwhile, the loss caused by the extraction can continue to be felt long after the financial benefit has run its course, particularly when externalities are not appropriately accounted for in regulation. This howtoregulate article looks at good examples of regulations with the objective of a sustainable natural resources sector.

A. International and supra-national regulatory framework

I. United Nations (UN)

1. There is no single, legally binding instrument that covers all the issues important to regulating the sustainable natural resources sector. However, the UN uses its good offices role and norm setting agenda to cover issues concerning the environment, protecting indigenous people’s interests and mining safety.

2. The UN Environment report on an Environmental Rule of Law shares best practices and good examples of regulation that protect the environment and states:

Experience has shown that political will is perhaps the most important consideration determining whether coordination [of environmental rule of law] will be successful.1

The report finds that environmental rule of law requires regular national assessment to meet the dynamic impacts that the environment sustains. Environmental rule of law also provides an important entry point for considering how to govern development so that it is sustainable. It recognises the difficulty in objectively measuring many aspects of environmental rule of law, including the quality of laws, the effectiveness of institutions, compliance rates, levels of corruption, or the respect for rights. UN Environment also partners with businesses to highlight the benefits of biodiversity-sensitive best practices in the mining sector.2

3. The UN has developed a System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA), which organises and presents statistics on the environment and its relationship with the economy. Such information would assist regulators better account for the externalities when considering extraction proposals. This information is brought together in a common framework to measure the conditions of the environment, the contribution of the environment to the economy and the impact of the economy on the environment. The SEEA contains an internationally agreed set of standard concepts, definitions, classifications, accounting rules and tables to produce internationally comparable statistics. The SEEA consists of:

- The SEEA Central Framework (2012) was adopted by the UN Statistical Commission as the first international standard for environmental-economic accounting in 2012.

- The SEEA Experimental Ecosystem Accounting offers a synthesis of current knowledge in ecosystem accounting.

- The SEEA Applications and Extensions illustrates to compilers and users of SEEA Central Framework based accounts how the information can be used in decision making, policy review and formulation, analysis and research.

4. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was adopted by the General Assembly in September 2007 and is the most comprehensive international instrument on the rights of indigenous peoples, particularly enjoyment of land rights and resources. The UNESCO Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage addresses the need for recognition of indigenous religious, cultural and spiritual rights, including their sacred sites in sustainable natural resources projects.

5. Other relevant UN conventions and guidelines that concern mining activities includes:

- C176 – Safety and Health in Mines Convention, 1995 (No.176);

- UNECE Convention on the Transboundary Effects of Industrial Accidents;

- UNECE Safety Guidelines and good practices for tailings management;

- Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution and its eight Protocols;

- Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes and its Protocol on Water and Health;

- Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context; and

- Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters.

II. World Bank

6. The World Bank provides technical assistance and loans to countries to promote policies and programmes that strengthen governance and environmental performance of the sustainable natural resources sector to ensure that benefits are widespread and sustained. The World Bank promotes the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative Standard among the countries it supports.

III. Organisation for Economic Development (OECD)

7. The OECD’s Mining Regions and Cities Project that aims to make policy recommendations for improving regional development outcomes for regions and cities specialised in mining and extractive industries. The 3 objectives of the projects is to 1) develop a global toolbox with recommendations and evidence to benchmark and inform regional development policies in mining, 2) produce a series of cases studies to help regions and cities to implement better policies and 3) develop a global platform for peer-review, knowledge-sharing and advocacy. The OECD has held annual project meetings since 2017, which enhances information sharing and lessons learned.

IV. European Union (EU)

8. The EU imports most of its raw materials, and due to volatility in such markets, it has developed an integrated strategy (Raw Materials Initiative) to respond to the different challenges related to access to non-energy and non-agricultural raw materials.3 The 2008 Raw Materials Initiative sets out targeted measures to secure and improve access to raw materials both within the EU and globally and the 3 pillars of the strategy are:

- Fair and sustainable supply of raw materials from global markets;

- Sustainable supply of raw materials within the EU; and

- Resource efficiency and supply of ‘secondary raw materials’ through recycling.

The EU also identifies Critical Raw Materials of particularly high risk of supply shortage in the next 10 years and which are particularly important for the value chain. The supply risk is linked to the concentration of production in a handful of countries, and the low political-economic stability of some of the suppliers.

9. The European Parliament (Directive 2013/34/EU) has transparency rules for public and large private extractive and logging companies, requiring them to publicly disclose the payments they make in excess of €100,000 to governments on a project-by-project basis (Chapter 10 Report on Payments to Governments of the Directive).

10. The EU has identified special protection areas in Natura 2000 which coordinates a network of core breeding and resting sites for rare and threatened species, and some rare natural habitat types which are protected in their own right. The network does not operate a strict system of nature reservation as most of the land is privately owned. The approach to conservation and sustainable use of the Natura 2000 areas centres on people working with nature rather than against it. Special rules apply to non-energy mineral extraction in or near Natura 2000 sites, which are outlined in Article 6 of the Habitats Directive and this Guidance Document explains how the resources sector can best ensure that developments are compatible with EU Directives.

V. African Union (AU)

11. The Africa Mining Vision is a policy framework for “transparent, equitable and optimal exploitation of mineral resources to underpin broad-based sustainable natural resources growth and socio-economic development” signed by AU Member States in 2009. The AMV sets out how mining can be used to drive continental development. The major interventions pf the AMV cover:

- Improving the quality of geological data;

- Improving contract negotiation capacity;

- Improving the capacity for mineral sector governance;

- Improving the capacity to manage mineral wealth;

- Addressing Africa’s infrastructure constraints; and

- Elevating artisanal and small-scale mining.4

The African Minerals Development Centre (AMDC)is responsible for implementing the AMV through the 54 AU Member States. The AMV is implemented through various Compacts targeting mining companies (including oil and gas); Chambers of Mines; and other mining associations. Each of the AMV Compact Principles are divided into ones for companies and one more Member States. For example Principle 1 provides that companies pay all mineral rents and royalties and ensure such actions are visible to the public.5 The States’ Principle 1 provides that all legal agreements with companies are published and that all government commitments to tax refunds and granting of permits are honoured in a timely and transparent manner.6 The remaining Principles can be found at this link.

VI. International multi-lateral groups

Several international multi-lateral groups have been successful in creating international norm, which are translated into national regulations, for the states that voluntarily sign up to the initiative.

Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI)

12. The global standard for the good governance of oil, gas and mineral resources is the EITI, which was launched in 2002 by then UK Prime Minister Tony Blair. The EITI Standard requires the disclosure of information along the extractive industry value chain from the point of extraction, to how revenues make their way through the government, and how they benefit the public7. The EITI consists of 53 implementing countries, majority of which are low-to-medium income countries with a handful of OECD countries. Fifteen countries support the EITI through public endorsement and assistance with financial, technical and political support at the international level. Implementing countries’ status of implementation from satisfactory progress to inadequate is assessed and recorded online. Like other international norm setting bodies, the EITI provides a secretariat function based in Oslo, Norway that coordinates implementation and assessment with national secretariats in implementing countries. Every three years implementing countries are quality assessed (validation) according to the EITI Standard to promote dialogue and learning at the country level. A multi-stakeholder EITI Board governs EITI and is made up of representative from governments, resources sector companies in the resources sectors, civil society organisations, financial institutions and international organisations.

13. Requirement 2 of the EITI Standard concerns disclosures on how the extractive sector is managed, its laws and procedures for the award of exploration and production rights, the legal, regulatory and contractual frameworks that apply to the extractive sector, and the institutional responsibilities of the State in managing the sector. EITI Requirement 2 specifically requires information about:

(2.1) legal framework and fiscal regime;

(2.2) public disclosure of contract and license allocations;

(2.3) register of licenses;

(2.4) contracts;

(2.5) beneficial ownership; and

(2.6) state participation in the extractive sector.

Further details about Requirements 1 and 3 through to 8 can be found here.

Publish What You Pay

14. Publish What You Pay is a global network (700 members) of grassroots civil society organisations working for transparency and accountability in the oil, gas and mining industries. The global network ask governments and companies to make public how much they receive and how much they pay for oil, gas and minerals. It promotes platforms which allow civil society representatives, companies and governments to collaborate, so that citizens voices are heard from the exploration to the exploitation stage. Publish What You Pay also provide opportunities for citizens to access, analyse, understand and use information so that they can meaningfully engage in discussions and decisions on how their natural wealth is managed.

B. National regulation

I. Sustainable Natural Resources Licensing Framework

1. Most jurisdictions operate a licensing framework to authorise the prospecting or mining/extraction of sustainable natural resources in the country. The licensing framework recognises that such resource ownership is vested in the state. For example Liberia’s Minerals and Mining Law 2000 provides at Section 2.1 “Minerals on the surface of the ground or in the soil or subsoil, rivers, streams, watercourses, territorial waters and continental shelf of Liberia are the property of the Republic and anything pertaining to their exploration, development, mining and export shall be governed by this law”. However, some jurisdictions recognise that particular minerals are vested in the indigenous people for cultural or customary rights reasons. New Zealand is one such example where the mineral of pounamu (geologically nephrite jade) is owned by the Māori people as per the Ngāi Tahu (Pounamu Vesting) Act 1997 and the Māori people have decided to not permit mining rights external to its tribal council.

2. There are at least two to three common licenses in the regulation of sustainable natural resources, and depending on the jurisdiction, there may be specific licences for particular minerals, each of which will be associated with different fees and conditions. Examples of common licences include8:

- A prospecting or exploration licence grants the holder an exclusive right to search for minerals within a defined area for a specified period and with conditions around the exploration. Some jurisdictions award reconnaissance licences (pre-exploration) for preliminary survey and testing work;

- A production licence grants the holder the exclusive right to extract minerals from a defined area for a specified period. Sometimes a retention licence is awarded, which grants an exclusive right over a deposit with no immediate requirement to develop the mine, usually in circumstances where market conditions are presently uneconomic. A production license generally covers a much smaller area than a prospecting licence, but is granted for a longer duration;

- Small-scale mining or artisanal mining licenses cover the subsistence miner who is not officially employed by a mining company, but works independently, mining minerals using their own resources, usually by hand; and

- Fossicking licences are for individuals prospecting for minerals usually as a recreational activity using hand tools.

3. The two examples of sustainable natural resources licensing explained in detail below, cover a simple framework (Ghana) and a complex framework (Western Australia, chosen on the basis of recent, March 2020, regulatory changes clarifying mandatory requirements). This howtoregulate article begins with the complex framework to better understand what requirements are not included in a simple framework. Other examples of jurisdictions that fall in between, and arranged by complexity, are listed with links to the respective licensing framework.

(a) Western Australia

4. The Western Australian (WA) state of Australia operates a complex licensing system of many different types of licences in its Mining Act 1978 (WAMA) for minerals. WA’s Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Resources Act 1967 (PGERA) and Petroleum (Submerged Lands) Act 1982 (PSLA) has 4 types of licences collectively known as Petroleum Titles. Applications for the major licences must be completed online and the licences that pertain to fossicking may be completed in person at the Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety (DMIRS).

WA Mining Act

5. WAMA licenses cover the common licenses above at paragraph 2 and the following procedures and rules apply:

(1) Miners Rights (Section 40 WAMA) are required for fossicking and prospecting, which is limited to Crown (state) land, proof of identity is required and, if a company, proof of incorporation9:

- Fossicking refers to the collection of mineral samples or specimens, other than gold or diamonds, for the purpose of a mineral collection, lapidary work or hobby interest.

- Fossicking on Crown land or conservation land, holders need prior written consent from land occupiers or mining tenement holders;

- Only hand tools may be used, including a metal detector but not machinery or machine based tools; and

- There is a limit of 20kg of samples or specimens that can be taken away at any one time.

- Prospecting is the search for all minerals including the use of metal detectors for the purpose of marking out land, and the holder may:

- pass and repass over Crown land for the purpose of prospecting and marking out any land which may be made the subject of an application for a mining tenement;

- prospect for minerals and conduct tests for minerals on Crown land that is not the subject of a mining tenement for the purpose of determining whether to mark out or apply for a mining tenement in respect of any part of the land;

- extract or remove from available land on each occasion, up to 20kg of samples or specimens of rock, ore or minerals with as little damage to the surface of the land as possible;

- take and use water from any natural spring, lake, pool or watercourse, including sinking a bore (latter subject to the Rights in Water and Irrigation Act 1914); and

- camp on any Crown land either in a vehicle or caravan, or a tent or other temporary structure, or in the open air, for the purpose of prospecting

- WAMA Section 40E Permits: Miner’s Right holders (other than companies) may apply for a permit to prospect for minerals on Crown land that are the subject of an Exploration Licence.

- The holder of a Miner’s Right is liable to pay compensation for any loss or damage caused and not made good by the holder. If compensation cannot be settled by agreement, the pastoralist or other lawful occupier of the Crown land may apply to the Warden’s Court for compensation to be determined.

- Miner’s Right holders are required to carry evidence of their Right, while fossicking or prospecting because failure to produce the Right when requested by a Police Officer or Authorised Officer incurs a penalty of AU$10,000.

- Conditions of a Miner’s Right:

- not use explosives or tools other than hand held tools;

- cause all holes, pits, trenches and other disturbances to the surface of the land to be backfilled and made safe;

- take all reasonable steps to prevent fire damage to trees or other property; and

- take all reasonable steps to prevent damage to property or to livestock by the presence of dogs, the discharge of firearms, the use of vehicles or otherwise.

(2) The WAMA prescribes the below mining tenements, each one prescribes area limits, limits to the number of licences a holder may have at the same time and depth limits:

- Prospecting Licences (Sections 40 to 56).

- Special Prospecting Licences for Gold (Sections 56A, 70 and 85B), prescribe minimum annual expenditure commitments and reporting requirements outlined in Regulations 16, 22, 23E and 32 of the WAMA.

- Exploration Licences (Sections 57 to 69E).

- Retention Licences (Sections 70A to 70M).

- Mining Leases (Sections 70O to 85A) require a security of AU$5,000 lodged with the application and must provide one of the following three documents:

- a Mining Proposal, which must be submitted for written approval by the Executive Director of the Resource and Environmental Compliance Branch of the DMIRS prior to the commencement of mining operations. See paragraph X for further details concerning requirements; or

- a statement about likely mining operations and a Mineralisation Report; or

- a statement about likely mining operations and a Resource Report.

- General Purpose Leases (Sections 86 to 90).

- Miscellaneous Licences (Sections 91 to 94) for purposes such as a roads and pipelines, or other purposes as prescribed in Regulation 42B.

6. The WA Statutory Guidance for Mining Proposals March 2020, represents the most detailed requirements for a number of categories found in the jurisdictions examined in this howtoregulate article. Mining Proposals must cover the following numbered items:

(1) Cover Page(s) must include information about tenement(s) and tenement holder or authorised company/person.

(2) Tenement holder authorisation: If the mining proposal is submitted by a person other than the tenement holder(s), then it must include authorisation from all tenement holders.

(3) Environment Group Site details: description of mining operation, commodity mined, estimated commencement and completion dates among other administrative information.

(4) Proposal Description: The mining proposal must include a description of the mining activities that are the subject of the proposal and how the mine will operate.

(5) Activity Details to be provided in the prescribed form at Appendix 1, which covers infrastructure and requires information about the area(s) of Key Mine Activities, such as (not exhaustive see Guidance for full list) dams, heap or vat leach facility, low-grade order stockpile (class1), Run-of-mine pad and Tailings or residue storage facility (classes 1 and 2).

(5.1) Additional Detail for Key Mine Activities (Appendix 2)

(5.2) Disturbance envelope: The mining proposal must include a disturbance envelope within which all activities will be contained, showing relevant tenement boundaries, tenement labels, and GDA (geographic latitude/longitude) coordinates in the prescribed measurement format

(5.3) Site Plan: The mining proposal must include an indicative map of the proposed layout of the mine activities in relation to the disturbance envelope and tenement boundaries.

(5.4) Tailings Storage Facilities: if proposed must include design report(s)

(6) Environmental Legislative Framework: The mining proposal must include a list of environmental approvals, other than under the Mining Act 1978, that have been sought or are required before the proposal may be implemented and any specific statutory requirements that will affect the environmental management of the site.

(7) Stakeholder Engagement: The mining proposal must include information on the engagement that has been undertaken with stakeholders, a record of the engagement undertaken to date and include a strategy for ongoing engagement.

(8) Baseline Environmental Data: The mining proposal must describe the existing environment in which the site is located, including any natural (biological/ physical) values and sensitivities and heritage areas that may be affected by the activities. This section must include a description of the baseline data covering the below environmental aspects as well as analysis and interpretation of the baseline data.

This section must cover the following environmental aspects:

-

- climate

- landscape

- materials characterisation (soils and geochemical and physical characteristics of subsurface materials and mining waste)

- biodiversity

- hydrology (including surface water and groundwater)

- heritage

- environmental threats.

Where environmental surveys or analysis has been undertaken the findings must be summarised in the mining proposal and all relevant technical reports must be attached as appendices.

(9) Environmental Risk Assessment: The mining proposal must include an environmental risk assessment that:

-

- identifies all the environmental risk pathways affecting DMIRS Environmental Factors across all phases of the mine life and that may arise from unexpected or emergency conditions;

- includes an analysis of these risks to derive an inherent risk rating, prior to the application of treatments;

- identifies appropriate risk treatments;

- includes an evaluation of the risk pathways to derive a residual risk rating; and

- demonstrates that all residual risks are as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP).

The mining proposal must provide information on the processes and methodologies undertaken to identify the environmental risk pathways and their potential environmental impacts, including a description of the risk assessment criteria and risk evaluation techniques.

(10) Environmental Outcomes, Performance Criteria and Monitoring: The mining proposal must include a table of site-specific environmental outcomes that the mining operation will achieve, along with performance criteria for each outcome. The proposal must also include a description of the monitoring that will be undertaken to measure each performance criteria.

(11) Environmental Management System: The mining proposal must include a description of the management system that will be implemented to appropriately manage all environmental risks.

(12) Mine Closure Plan.

(13) Expansions and/or Alterations to an Approved Mining Proposal: In addition to the above information, revised mining proposals for the expansion and/or alteration to approved activities must also include:

-

- an updated document revision number to indicate that the document is a revision to a previously approved mining proposal; and

- a revision summary table that clearly outlines all changes made in the revised mining proposal.

7. The Mining Proposals for small mining operations requires the following topics to be covered:

(1) Cover Page.

(2) Tenement holder authorisation.

(3) Scope of Works.

(4) Site Layout Plan.

(5) Existing Environment.

(6) Area of Disturbance.

(7) Waste Rock/Tailings/Mine Waste Management.

(8) Dust/Noise.

(9) Water.

(10) Land Use and Stakeholder Engagement.

(11) Environmental Management Commitments.

(12) Mine Closure Plan.

To be considered small mining operations:

(1) The activities must not be for the mining of uranium, mineral sands or rare earth elements; and

(2) The activities must be limited to the following activities:

a. Scraping and detecting.

b. Dry blowing.

c. The following activities for a total footprint in the mining proposal of 10 hectares (ha) or less:

i. Mining excavations (pits, costeans, quarries, shafts, winzes, harvesting, dredging), leaching operations and tailing treatment operations.

ii. Any construction activities incidental or conducive to the activities including plant, tailings storage facilities and overburden dumps.

WA Petroleum Acts

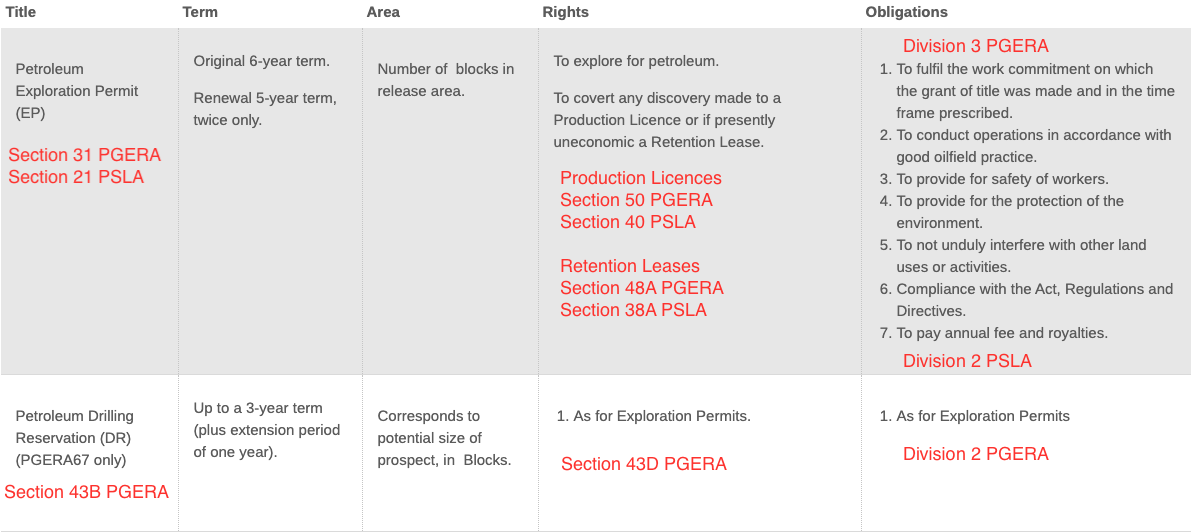

8. A summary of obligations and conditions for each petroleum licence type can be found in the below table from the WA DMIRS website (legislative provisions annotated in red):

Petroleum Titles are permitted to be transferred on application, under Section 72 PGERA and Section 78 PSLA82. If the assuming title holder (transferee) is not a registered holder, information about the following shall be included in the application for transfer [Section 72(3)(b)]:

- the technical qualifications of that transferee or those transferees; and

- details of the technical advice that is or will be available to that transferee or those transferees; and

- details of the financial resources that are or will be available to that transferee or those transferees.

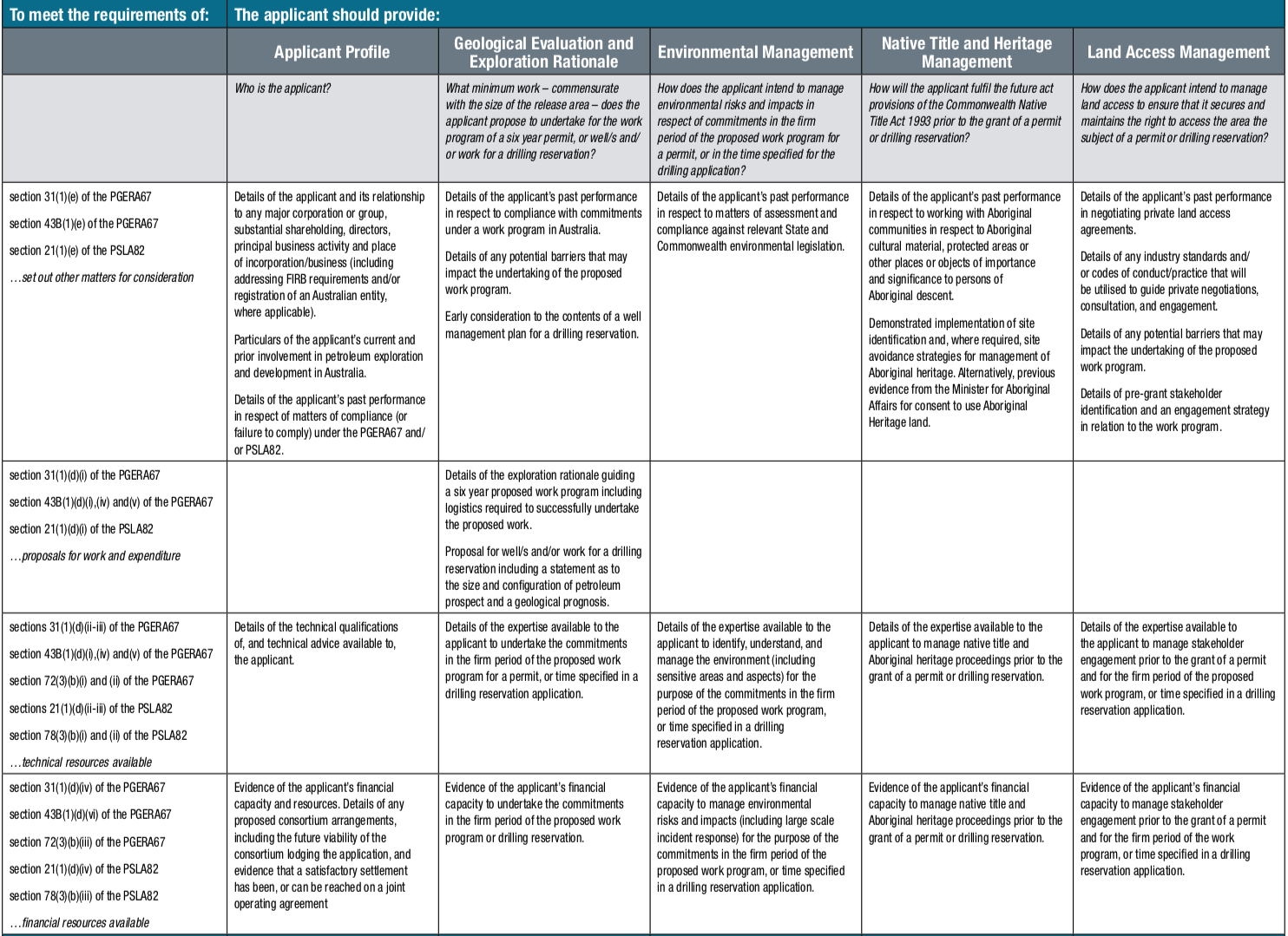

9. WA also operates a competitive bidding process for Petroleum Titles under Section 30 and Section 43A of the PGERA and Section 20 of the PSLA whereby the Minister invites applications for the grant of a petroleum exploration permit or petroleum drilling reservation. Under Section 105(3(a)(ii) of the PGERA, the Minister may authorise the registered holder of a special prospecting authority to apply for the grant of a petroleum exploration permit or petroleum drilling reservation, commonly called the acreage option. The exception to the periodic release process is applications for Special Prospecting Authorities with an Acreage Option. Petroleum Exploration Permits are awarded to bidding applicants whose work programmes undertake the widest assessment of an area’s petroleum potential. Other focus areas include sound resource management, safety and environmental principles, and the ability to satisfy the criteria for assessment guidelines, which apply equally to sole or competitive bids. The WA assessment guidelines provide additional information to applicants about the assessment criteria which covers various sections of the two petroleum acts but cover the following requirements:

- Applicant profile: Who is the applicant and information about transparency requirement around their petroleum experience and past performance, technical qualifications, evidence of financial capacity and resources.

- Geological evaluation and exploration rationale: What minimum work – commensurate with the size of the release area – does the applicant propose to undertake for the work programme of a six year permit, or well/s and/ or work for a drilling reservation?

- Environment management: How does the applicant intend to manage environmental risks and impacts in respect of commitments in the firm period of the proposed work program for a permit, or in the time specified for the drilling application?

- Native Title and Heritage management: How will the applicant fulfil the future act provisions of the Commonwealth Native Title Act 1993 (federal legislation) prior to the grant of a permit or drilling reservation?

- Land access management: How does the applicant intend to manage land access to ensure that it secures and maintains the right to access the area the subject of a permit or drilling reservation?

A table summarising the legislative criteria and explanatory information is found at Annex 1.

(b) Ghana

10. Ghana’s Minerals and Mining Act, 2006 (Act 703) provides a simple licensing framework of four types of licences:

- Reconnaissance licence (Sections 31-33) for an initial period of not more than twelve months and for an area not more than five thousand contiguous blocks (block size defined at Section 8 Cadastral system);

- Prospecting Licence for an initial period of not more than three years and for an area not more than 750 contiguous blocks(Sections 34-38);

- Mining lease: term is for 30 years, Government shall acquire (without paying) 10% free carried interest in the rights and obligations of the mineral operations (Sections 39-61); and

- Small scale mining licences (Sections 81-99) are awarded to citizens of Ghana (who may be a person, a group of persons, a cooperative society or a company), who are 18 years old or more and is registered by the office of the Commission in an area designated under Section 90 (1). The duration of the licence is not more than five years, is exclusive and may be transferred.

11. Ghana’s Petroleum Commision established by Act of Parliament, 2011 (Act 821), regulates and manages the use of petroleum resources and coordinates the policies in the upstream petroleum sector. The Petroleum (Exploration & Production) Act, 2016 [Act 919] provides that “petroleum activities shall be conducted in an open area under a licence or petroleum agreements” (Section 5). The Minister decides the open area (Section 7), following conclusion of an evaluation report that considers:

- the impact on local communities,

- impact on the environment, trade, agriculture, fisheries, shipping, maritime and other industries and risk of pollution, and

- the potential economic and social impact of the petroleum activities.

This evaluation report must be published in the Gazette and in at least two state-owned daily newspapers and may publish in another medium of public communication. A person who has an interest in an area which is the subject of the evaluation report shall, within sixty days after publication of the evaluation report, present his/her views to the Minister. Based on the report and any views received, the Minister shall determine whether or not to open an area.

12. Reconnaissance licences are awarded by the Petroleum Commission and grant the licensed person a non-exclusive right to undertake data collection, including seismic surveying and shallow drilling (Section 9 of Petroleum Act). The Minister may in a special case grant to a person an exclusive right to undertake reconnaissance activities but such a grant does not affect any proprietary rights of Ghana to data or preclude the rights of the Commission or the Corporation (see National Petroleum Corporation Law below) to undertake reconnaissance or other petroleum activities in the same area [Section 9(3) Petroleum Act]. The reconnaissance activity shall not commence until the relevant statutory provisions on environmental protection prescribed by the Environment Protection Agency Act, 1994 (Act 490) and any other applicable enactments have been complied with [Section 9(6) Petroleum Act].

13. The Ghana National Petroleum Corporation (state-owned company) established by the National Petroleum Corporation Law, 1983 (PNCL 64) mandate the corporation to engage in exploration, production and disposal of petroleum products. The PNCL forms the legal structure of contractual agreements between the Government of Ghana and private oil exploration companies. Petroleum agreements are awarded following an open, transparent and competitive public tender process to a body corporate (the contractor) for petroleum exploration, development and production in accordance with the terms entered into between Ghana and the Corporation (Section 10 Petroleum Act. However, the Minister does have discretion to not award a petroleum agreement after a tender process and if the Minister determines that it is in the public interest for that area to be subjected to a petroleum agreement, the Minister may initiate direct negotiations with a qualified body corporate [Section 10(9) Petroleum Act]. A petroleum agreement shall be ratified by Parliament [Section 10(13) Petroleum Act]. A petroleum agreement shall be for a duration of not more than 25 years (Section 14 Petroleum Act). Shares in a petroleum agreement may be transferred following approval from the Minister and the Petroleum Commission (Section 25 Petroleum Act). The contractor shall ensure that development and productions of petroleum is conducted in accordance with best international practice and sound economic principles, and in a manner that will ensure that waste of petroleum or loss of reservoir energy is avoided (Section 26 Petroleum Act). Once discovery is made, the contractor must submit a plan of develop and operation that provides detailed information on the economic, reserves, technical, operation, safety, commercial, local content and environmental components (Section 27 Petroleum Act).

14. Regulatory information about the licensing systems of the following jurisdictions can be found at the following links:

- Chile’s mining regulation is complex based on legal provisions that were enacted as part of the Constitution (1980) and include the Organic Constitutional Law on Mining Concessions (Law No. 18,097) and the Mining Code (1983), details of which can be found here.

- Canadian state of Ontario’s Mining Act 1990 is also complex but not as complex as WA’s, commentary can be found here.

- Nigeria’s Minerals and Mining Act, 2007 (Act No. 20), example of a regulation of medium complexity, commentary can be found here.

II. Enforcement of mining regulations and empowerments of mining regulators

15. WA has provided a clear enforcement policy for the eight legislative acts and their associated regulation to “guide the [regulator-DMIRS] in exercising its enforcement responsibilities [and to] explain to stakeholders and the community how [it] approaches its statutory enforcement responsibilities”. Decisions to use enforcement action will take into account a number of factors, including:

- cooperation and willingness to take remedial action;

- culpability – whether there is significant risk, serious harm or an activity that results in significant breaches of the legislation;

- due diligence procedures in place;

- failure to notify the Department;

- failure to comply with either a legal direction or notice, or previous noncompliance;

- level of public concern or interest;

- mitigating or aggravating circumstances;

- need for specific or general deterrence; and

- precedent which may be set by any failure to take enforcement action.

Some of the empowerments include, but are not limited to, the following:

- giving advice on compliance and seeking voluntary compliance;

- negotiating responses and requesting action;

- issuing a direction or warning;

- issuing an improvement or prohibition notice;

- issuing a remediation notice or an improvement notice;

- issuing an infringement notice and fine;

- accepting an enforceable undertaking;

- amending permit or tenement conditions;

- revoking, suspending or cancelling authorisations or licences;

- seeking an order or injunction;

- commencing forfeiture proceedings;

- commencing a criminal prosecution; and

- publishing enforcement actions and outcomes.

WA also has guidelines for prosecutions action to court.

III. Regulatory techniques for the objective of transparency in the sustainable natural resources sector

16. Canada’s Extractive Sector Minerals Transparency Act (ESTMA) is a good example of a comprehensive regulation of transparency in the sustainable natural resources sector, notable given that Canada is a significant global mining exporter. Key features of ESTMA, include:

- Broad scope of obligations applies to Canadian companies’ activities in Canada and abroad as well as foreign multinationals with a presence in Canada, as well as private equity firms that own a small oil, gas or mineral operation somewhere within their corporate structure (Section 8).

- Mandating project-level disclosure allows local governments and local populations to determine whether they are getting their fair share of the benefits derived from resource extraction taking place within their jurisdictions, for example in some areas (such as in the Democratic Republic of Congo), local provinces and municipalities are entitled to shares in mining project revenues that occur in their territory.10

- Reports on disclosures are required to be publicly available (Section 12) and are found here.

- The Minister has the ability to order any entity subject to ESTMA to provide an independent audit of compliance.

- Appropriate fines for failing to publish a report, knowingly making misleading statements in the report, or trying to structure payments to avoid including them in the report (e.g., characterising certain payments as “gifts” or lumping them improperly with other items) is a summary offence, punishable by a fine of up to $250,000 (Section 24).

17. Liberia’s mining laws are a good example of a simple regulatory scheme representing international best practice such as removal of discretionary powers and transparency in licensing procedures. The New Minerals and Mining Law 2000 (NMML) governs the minerals within the territory of Liberia and the Liberia Exploration Regulations govern the administration of exploration licences issued under the NMML. Liberia’s Ministry of Mines & Energy maintains a comprehensive website with all the laws that a mining licensee must comply with, a public register of licence holders, mineral potential map, mining deposits and all licenses and related payments. Key features of the Liberian mining regulation, include:

- List of persons or individuals not eligible for mining rights (Section 4.2 of NMML), inter alia Liberian public officials such as President, Vice President, any member of the National Legislature, Justices of the Supreme Court and Judges of subordinate courts of record, Cabinet Ministers and Directors of Public Corporation during their tenure in office. Section 4.2 also states that where such an official already is a Holder of a Mineral Right prior to assuming the functions of the office that Holder may either dispose of the right to place such a right in a blind trust.

- Section 10.1 of the NMML lists lands not subject to mineral rights such as Poro or Sande cultural grounds, cemeteries, grounds reserved for public purposes, except wth the consent of the officials authorised to administer the affairs of such entities.

- Chapter 15 of the NMML regulates the trading and dealing in gold, diamonds and other precious metals.

- Schedule 13.2(b) of the regulations requires a Licensee to submit for each site at which pilot mining is proposed, compliance with the reporting requirements of the Kimberley Process and EITI.

- Child labour is prohibited (Section 16.10).

- Establishment of a Mineral Development Fund from sources proscribed in the NMML eg 25% of mineral royalties, one-off payment of US$50,000 from the Holder of a Class A Mining License or by each person who is a party to a Mineral Development Agreement with government and amounts collected from fines imposed (Section 18.3 NMML).

- The Mineral Development Fund is to fund promotion of safety standards, environmental assessments, training of public servants and education and training for operators engaged in small scale mining (Section 18.4 NMML).

18. These EITI implementing countries have requirements about the beneficial owners of companies holding either mineral or petroleum rights:

- UK has legislation requiring beneficial ownership to be recorded on its public company registry;

- Madagascar does not have legislation in place but does provide EITI reports on who some of the beneficial owners of companies in their mining sector are;

- Security Exchange Commission of the Philippines issued a Memorandum about collecting beneficial ownership information;

- Mongolia asked entity holders of 5% or more of a mining or petroleum licence to voluntarily disclose their beneficial owners; and

- Progress on all EITI Implementing Countries can be found here.

The howtoregulate article “Beyond a destination and towards a culture: Corporate transparency regulations” analyses various jurisdictions approach to regulating beneficial ownership.

IV. Regulatory techniques for the objective of public and worker safety to maintain sustainable natural resources.

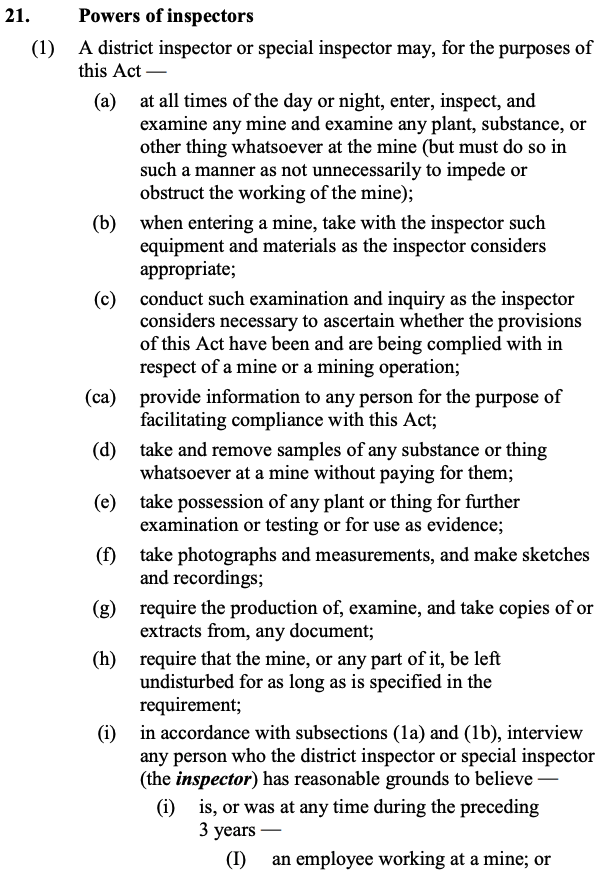

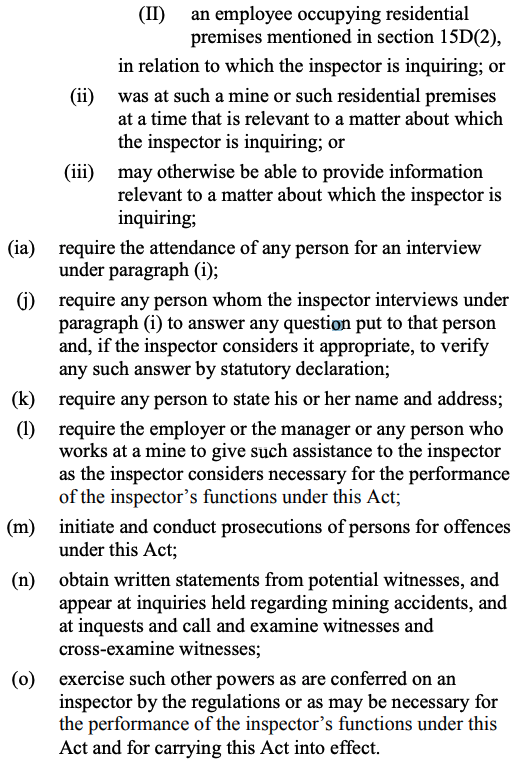

19. In WA there is specific sustainable natural resources sector legislation regulating safety. The principal legislation is the Mines Safety and Inspection Act 1994 (MSIA) which imposes general duty of care provisions to maintain a safe and healthy workplaces at mining operations and protect people at work from hazards. The obligations apply to the following groups: Part 2, Division 2 (employers and employees) and Part 2, Division 3 (contractors and their employees, labour hire agents and workers and people involved in the design, supply installation and maintenance of the mining plant). The groups identified have their respective obligations, including penalties for breaches to help prevent unsafe situations. In hazardous situations, an employer or self-employed person has a duty to report hazardous situations, and must give notice of the situation as soon as reasonably practicable, failure of which is an offence (Section 15F). Other important features of the MSIA includes:

- The inspectors of mines are the State mining engineer, State coal mining engineer, and the State mining engineer [Section 16(4)] and their appointments and competencies are regulated by Part 3, Division 1.

- Section 18(3) provides for the appointment of Special inspectors for the purpose of making inspections, inquiries and investigations that require technical or scientific training or knowledge as director by the State mining engineer.

- Part 3, Division 2 concerns the empowerments of such inspectors, which are broad and powerful:

- Section 24 concerns complaints to inspectors, which can be made by any person working at a mine and the inspector must inquire into the complaint.

- Section 29 provides that a person must not obstruct, hinder or interfere with an inspector acting lawfully, a contravention by a person is an offence.

- Division 3 concerns the improvement notices (Section 30) and prohibition notices(grounds for which are found at Section 31AB) issued by an inspector and how compliance must be performed. Failure to comply to either notice is an offence.

- Notices may be referred to Tribunal for review and the Tribunal may confirm, vary or revoke a decision or determination of the State mining engineer (Section 31BB).

- Part 4 concerns the management of mines, outlining the roles and duties of important persons at the mine eg. underground manager, quarry manager, exploration manager and the requisite certificates of competencies for each rule.

- The inspector or a person may make a complaint to a Board of Examiners where that person believes that the holder of a certificate of competency is incompetent or unfit to perform his or her duties (Section 49).

- Part 5, Division 2 concerns the establishment, roles and functions of a safety and health committee at a mine.

V. Regulatory techniques for protecting community interests and indigenous rights and heritage to maintain sustainable natural resources.

20. New Zealand’s Resources Management Act 1991 (RMA) provides that no persons or companies can do anything affecting the environment, including extracting sustainable natural resources, unless the activity is permitted in a local authority plan, which involves community and indigenous communities in the decision-making process. The purpose of the RMA at Section 5(1) “is to promote the sustainable natural resources management of natural and physical resources.” and sustainable natural resources management is defined at Section 5(2):

In this Act, sustainable natural resources management means managing the use, development, and protection of natural and physical resources in a way, or at a rate, which enables people and communities to provide for their social, economic, and cultural well-being and for their health and safety while—

- sustaining the potential of natural and physical resources (excluding minerals) to meet the reasonably foreseeable needs of future generations; and

- safeguarding the life-supporting capacity of air, water, soil, and ecosystems; and

- avoiding, remedying, or mitigating any adverse effects of activities on the environment.

21. While the RMA provides an overarching guide on what’s best for the environment, with national direction on significant issues (Section 6 Matters of national importance), it allows communities to make decisions on how their own environment is managed through regional and district resource management plans. This framework means that most decisions on resource management are made by local government who are closest to the communities that are most likely to be affected by the exploration and extraction of sustainable natural resources.

22. If persons or companies wish to extract resources from the environment, including seabed out to the 12 nautical mile boundary, that is not already permitted by a local authority, then resource consents must be sought from the appropriate local authority (Part 6 Resource Consents). Decisions on resource consents are made by RMA hearing panels with consideration to local plans, national direction and the objectives in the RMA. The requirement is for all members of RMA hearing panels, given authority by a local authority under Sections 33, 34, or 34A, to be accredited, unless there are exceptional circumstances (Section 39B). The Making Good Decisions Programme helps councillors, community board members, and independent commissioners make better decisions under the RMA.

23. The RMA also recognises the Treaty of Waitangi (Section 8) and Section 66 of the RMA requires plans to consider customary rights of Māori. In theory, it may be possible for Māori people to veto a land use although this has not been tested.11

VI. Regulatory techniques for the objective of environmental protection

24. The UN Global Report on Environmental Rule of Law recommends regular assessment of a nation’s environmental rule of law to determine if it remains fit for purpose. It suggests that although enforcing existing laws is critical, the ultimate goal of environmental rule of law is to change behaviour by creating an expectation of compliance with environmental law coordinated between government, industry, and civil society. The report lists many examples of regulatory techniques used by countries to strengthen environmental safeguards in the resources sector. Such examples include:

- Ghana’s AKOBEN programme which is an environmental performance rating and disclosure initiative of the Ghana Environmental Protection Agency. Under the AKOBEN initiative, the environmental performance of the 16 largest mining and 100 largest manufacturing operations is assessed using a five-color rating scheme that indicates environmental performance ranging from excellent to poor. These ratings are performed by the government and annually disclosed to the public and the general media, and they aim to strengthen public awareness and participation.12

- Mexico’s voluntary Environmental Auditing Program encourages organisations to be voluntarily evaluated by independent auditors for compliance with environmental laws and regulations. Organisations agree to correct any violations by a certain date in exchange for a commitment by the Mexican Attorney General for Environmental Protection not to take enforcement action until after that date. If the organisation meets the compliance requirements, it receives certification as a Clean Industry; if it goes beyond the requirements to achieve certain pollution prevention and eco-efficiency guidelines, then it receives a certification of Environmental Excellence.13

- Malaysia adopted standard operating procedures applicable to all enforcement officers. These procedures are comprehensive and cover: development of annual inspection programs; prioritisation of sectors to be the focus of enforcement efforts based on previous compliance and non- compliance; procedures to be followed during inspection and investigation; methods for sampling and collecting evidence; guidance on recording statements; procedures for issuing detention orders and prohibition orders to stop specific pollution; and preparation of documents for referring matters to the Attorney General for prosecution.14

25. Liberia has outlined in its Exploration Regulations the duties of exploration licensee’s at Section 10.1:

A Licensee must in any event take preventive or corrective measures to ensure that all streams and water bodies within or bordering Liberia, all dry land surfaces, and the atmosphere, are protected from pollution, contamination or damage resulting from exploration operations pursuant to its Licence, and shall construct its access roads and other facilities so as to limit the scope for erosion and the felling of mature trees. If the exploration operations of a Licensee violate any requirement referred to in this Section or otherwise damage the environment, the Licensee must proceed diligently to mitigate and/or restore the environment as much as possible to its original and natural state and to take preventive measures to avoid further damage to the environment.

26. It is a common requirement of mining licence holders to rehabilitate the environment once the mine closes and that a security is required to be lodged before extraction activities start.

- The West Australian Mining Act 1978 provides at Section 26(1)(a) “any person carrying out mining operations on the land shall make good injury to the surface of the land or injury to anything on the surface thereof” and at Section 26(1)(d) “shall lodge with the Minister, within such period as the Minister specifies in writing, a security to cover the probable cost of the work”.

- Ontario Regulation 240/00, Mine Development and Closure under Part VII of the Mining Act, is the regulation which sets out how mine closure plans and the associated financial assurance (i.e., reclamation security) are developed, assessed and administered.18

- The Liberia Exploration Regulations at Section 10.3 concerns the security for remediation and restoration of land subject to exploration, which is equal to 15% of the budget for its approved work plan. The security must be provided as a letter of credit or in another form satisfactory to the Minister of Finance.

27. In 2016, Norway’s Standing Parliamentary Committee on Energy and the Environment recommended, and was adopted, to prohibit deforestation in the National Biodiversity Action Plan15. Specific goals include zero deforestation in Norway’s public procurement, encouraging deforestation-free supply chains and investments through the Government Pension Global Fund (GPGF)(one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world)16. This will affect the GPGF’s future investment in extractive industry companies, possibly involve divestment from GPGF where such companies are noncompliant with deforestation and the importation of goods or materials linked to deforestation. The government also cannot grant contracts to companies involved in deforestation.17

C. Conclusion

What is striking in the sustainable natural resources sector is that best practice regulation and guidelines, at the national, international and multi-lateral level are abundant as are the financial resources to implement standards given the wealth of the sector. While no one jurisdiction makes use of all the good regulatory techniques outlined in this howtoregulate article on “Regulation for the Sustainable Natural Resources Sector tp Infinity and Beyond” for reasons such as different legal systems, institutional experience and market conditions, most jurisdictions regulate the following to some degree:

- licences;

- enforcement measures;

- empowerments;

- engagement with extractive industries-affected stakeholders eg landowners, communities, indigenous people; and

- protecting the environment.

It is evident from examining the mining regulations for sustainable natural resources that those jurisdictions that provided clear and detailed requirements on the above five points, along with limiting discretionary decision-making, tended to have less fatal mining accidents, less conflict with stakeholders, and fewer environmental disasters.

This article on “Regulation for the Sustainable Natural Resources Sector tp Infinity and Beyond” was written by Valerie Thomas, on behalf of the Regulatory Institute, Brussels and Lisbon.

Links

International Bar Association, Model Mine Development Agreement (2011)

International Finance Corporation, Policy on Environmental and Social Sustainability (2012) requires that loans be disclosed

Responsible Mining Index by Responsible Mining Foundation

Mining laws database ICLG https://iclg.com/practice-areas/mining-laws-and-regulations

World Bank Guiding Template on mining law drafting

World Bank Sector Licensing Studies on the Mining Sector

Annex 1

(https://www.dmp.wa.gov.au/Documents/Petroleum/PD-PTLA-AR-106D.pdf)

1 UNEP, First Global Report on the Environmental Rule of Law, 2019, Chapter 6 Future Directions p. 234, https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/27383/ERL_ch6.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

2 UNEP News, “Moving the global mining industry towards biodiversity awareness”, https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/moving-global-mining-industry-towards-biodiversity-awareness.

3 Farooki, M. et al, “Supporting the EU Mineral Sector: Capitalising on EU strengths through an investment promotion strategy”, September 2018, pp. 3-5, https://www.stradeproject.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/STRADE_EU_Mining_Sector_Support_Sept2018.pdf.

4 Oxfam Briefing Paper, “From Aspiration to Reality Unpacking the Africa Mining Vision”, March 2019, pp. 8-10, https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/bp-africa-mining-vision-090317-en.pdf.

5 African Union and UN Economic Commission for Africa, “Africa Mining Vision Looking Beyond the Vision”, 2017, p. 8, https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiJiemOv4D6AhUEgHMKHYBLDhwQFnoECAwQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Farchive.uneca.org%2Fpublications%2Fafrica-mining-vision-looking-beyond-vision&usg=AOvVaw2IVacG8GSRWt5-_Co4B7snhttps://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/PublicationFiles/africa_mining_vision_compact_full_report.pdf.

8 World Bank document, Sector Licensing Studies: Mining Sector, p. IX, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/867071468155129330/pdf/587890WP0Secto1BOX353819B001PUBLIC1.pdf.

9 WA Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety, Miner’s Rights, https://www.dmp.wa.gov.au/Documents/Minerals/Miners_Rights.pdf.

11 Ruchstuhl, K. et al, Maori and Mining, 2013, https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/handle/10523/4362.

12 UN Environment, Environmental Rule of Law Global Report, p. 76, https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/assessment/environmental-rule-law-first-global-report.

18 Stantec Consulting, Policy and Process Review for Mine Reclamation Security, September 2016, p. 3.2, https://eiti.org/sites/default/files/documents/gheiti_2014_mining_sector_report_0.pdf.

15 Rainforest Foundation Norway, “Norwegian state commits to zero deforestation”, 26 May 2016, https://www.regnskog.no/en/news/norwegian-state-commits-to-zero-deforestation-1.

16 Natural Adventures, “Norway is the world’s first nation to ban deforestation”, 28 January 2020, https://www.nathab.com/blog/norway-is-the-worlds-first-nation-to-ban-deforestation/.

17 Business Insider, “11 fascinating environmental protections and laws around the world”, 29 April 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/environmental-rules-laws-protections-around-the-world-2019-4.