Legislative and regulatory acts (hereafter jointly called “acts”) rarely exist in an isolated way. Therefore, it is important to fit them well into the overall regulatory architecture for the given sector or field. We examine in this howtoregulate article how best to position an act in the overall regulatory architecture. To that end, we need to look more closely at how acts relate to each other.

2. Acts can relate to each other in different ways. One parameter of distinction is the degree of independence between the two acts. The different acts can be applicable in parallel, independently one from another, e.g. when they deal with different sectors or when they deal with different aspects regarding the same sector. Or one act can refer to the other and make the other act thus applicable. In between are cases where there is in principle independent, parallel applicability, but one act modifies to a certain extent the other.

3. Another parameter is the degree of abstraction. The different acts can occupy different levels of abstraction.

4. Already from these two parameters, we can derive a multitude of architectures. Hence the question arises how the overall architecture of regulation is best built. “Best” means here: consistent, efficient, based on best practices across various sectors, without redundancies and user-friendly. There are quite some choices to be made with regard to the architecture of regulation.

5. In order to develop a good architecture, it is necessary to analyse the similarity of requirements and other provisions that need to be applied to different sectors (in the following, we refer only to requirements whilst other provisions might also need to be taken into account). The knowledge about these requirements influences the decision on the best architecture. The more that requirements are similar or even identical, the easier it is to place them at a higher level of abstraction, into horizontal or semi-horizontal acts.

6. Regulators of a particular sector may overestimate the specificity of their requirements. Many regulators of specific sectors think that their sector requirements are extremely specific. They often do so because they have not extensively studied the requirements set up in other sectors. The more one reads regulation of different sectors, the more one recognises that requirements are in essence similar, but just formulated in different ways. These differences are to a certain extent due to the sector’s specificities and thus justifiable. But often they are also simply due to the fact that the regulators of one sector conceive of requirements better or worse than in another.

I. Four basic models of architecture

7. First we present below two extreme models, as the remaining two fall between these extremes:

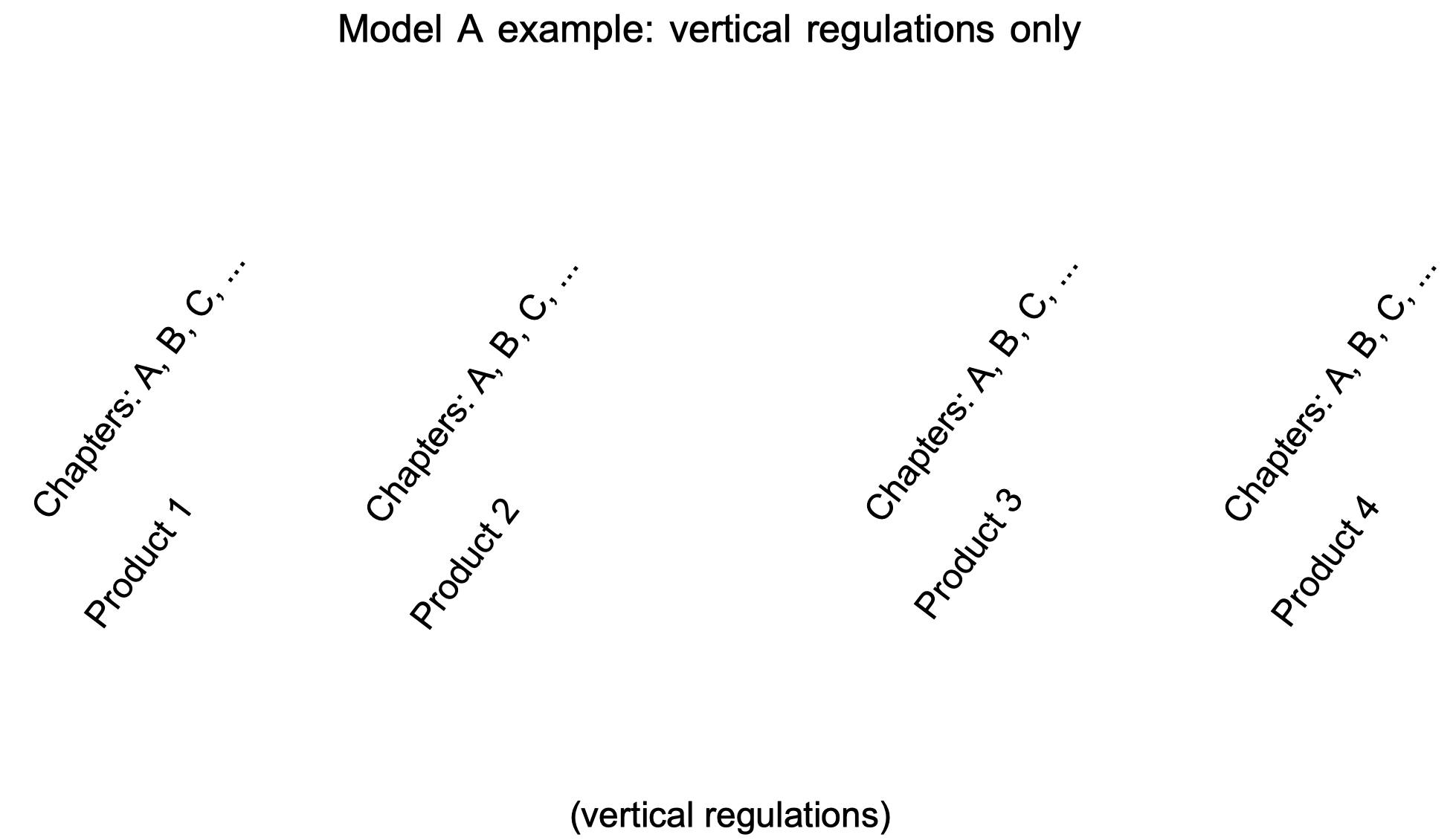

Model A: All provisions are in a sector specific (vertical) act even though the other sectors of the same type contain identical provisions:

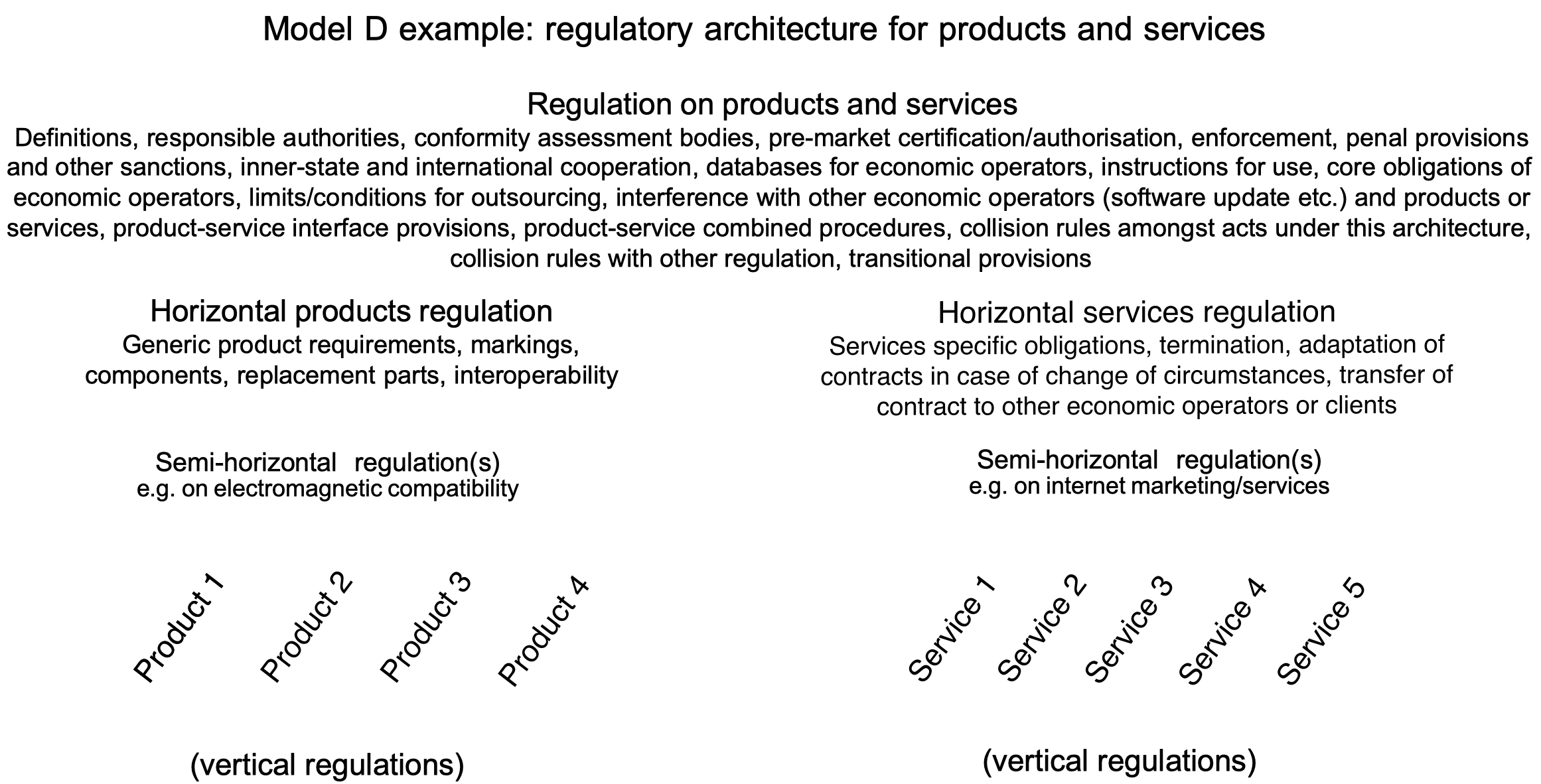

8. Model D: Different acts apply in parallel to one and several sectors, and these acts have different positions in the graph below. Some acts apply to many sectors / all sectors of the same type (horizontal acts), some acts apply to a few sectors (semi-horizontal acts), and finally there are acts that apply only to one sector (vertical acts). Individual provisions are placed at the highest possible level, meaning in horizontal acts where they apply to all sectors, in semi-horizontal acts where they apply only to a few sectors, and in vertical acts where they apply only to one sector. We illustrate Model D as a potential architecture for regulating products and services. However, we have unfortunately not yet seen an example of Model D regulatory architecture anywhere in the world:

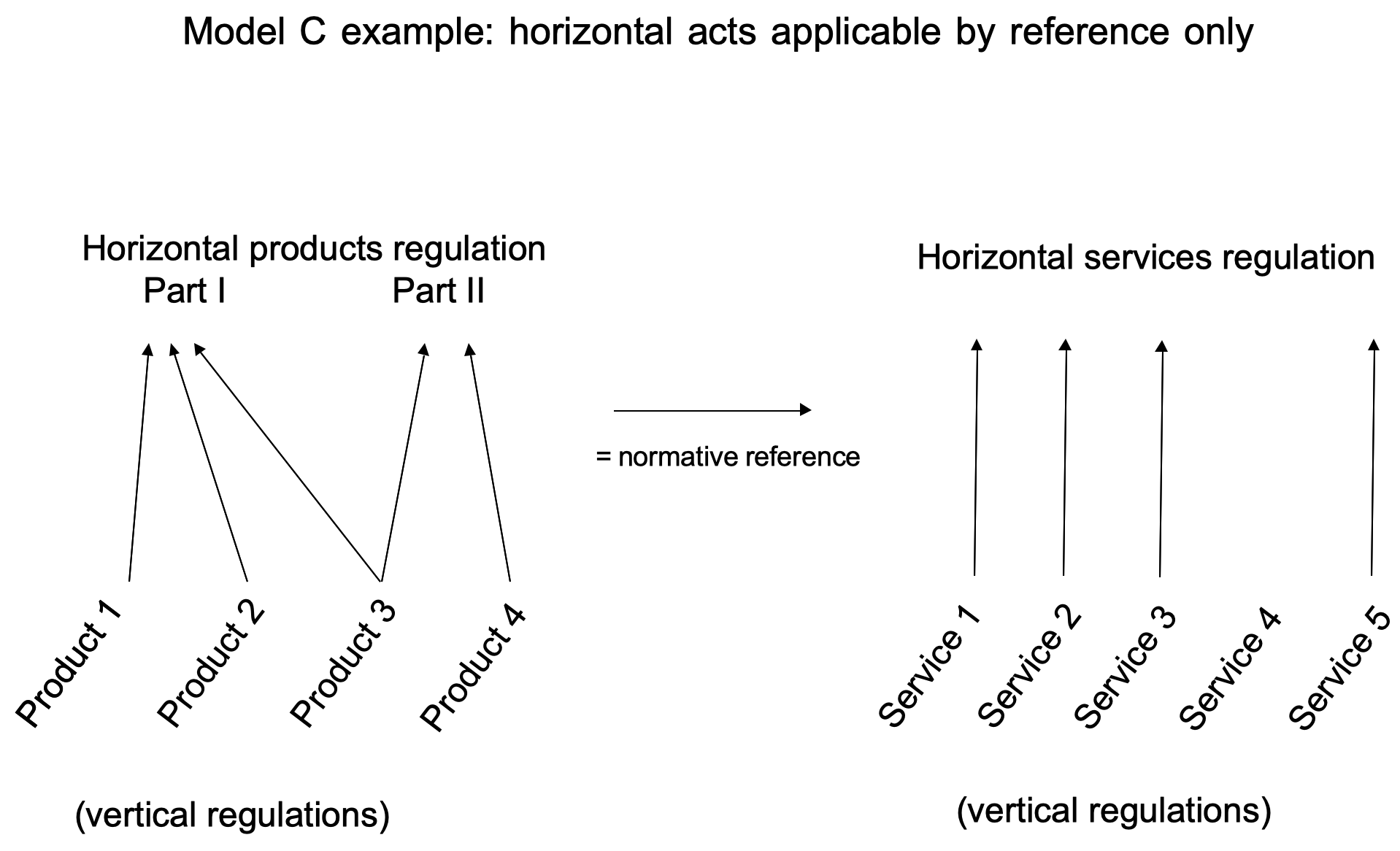

9. Model C: In Model D, the horizontal and semi-horizontal acts are applicable by themselves (“eo ipso”). In Model C, however, they are not applicable by themselves, but only due to the fact that vertical acts normatively refer to them. See as an example Section 10 of the Brazilian Portaria INMETRO / MDIC Number 2471 of 26/05/2014 on the conformity assessment for the retreading of tires. It refers to a horizontal act, but also contains certain sector specific provisions. Here an example:

“The criteria for responsibilities and obligations must follow the ones below and those established by the RGDF.”

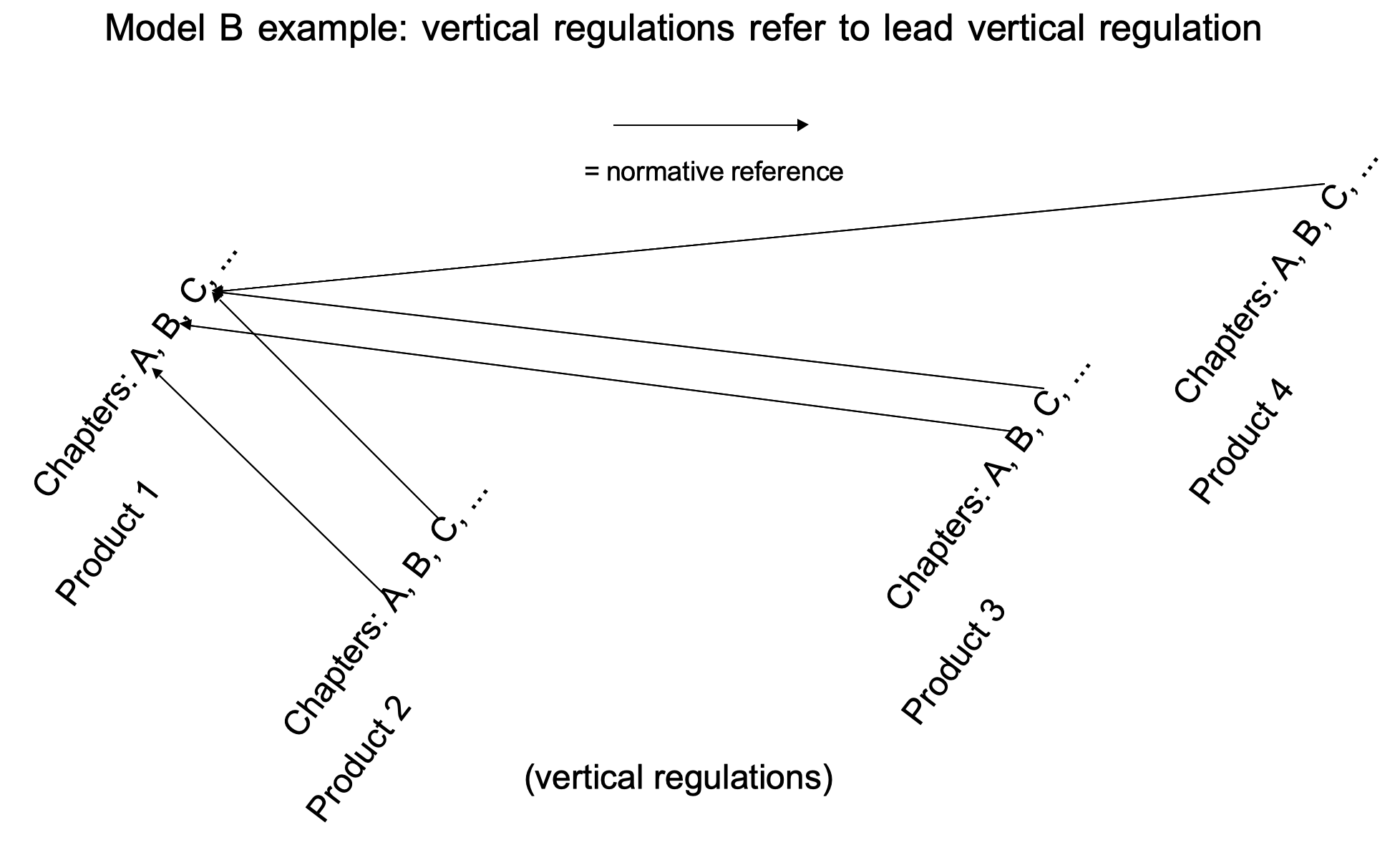

10. Model B: Similar to Model A, Model B consists only of vertical acts but in Model B, there is a “lead vertical act” to which the other vertical acts normatively refer to. The normative reference can be triggered by provisions like: “Chapter A of Act XYZ applies” or “Chapter A of Act XYZ applies by analogy”.

See our howtoregulate article “Typology of referencing in regulations” about best practices for normative references or citations.

See our howtoregulate article “Typology of referencing in regulations” about best practices for normative references or citations.

II. Advantages and disadvantages of these models

11. Model A has the advantage that users only need to read one single act. Moreover, there is no risk that the sector is exposed to inappropriate horizontal requirements. But Model A has several disadvantages:

- There is a risk that the different sectors (vertical acts) develop unjustified specificities and other deviations so that economic operators and persons are exposed to a variety of mostly not optimised and inconsistent requirements.

- This is annoying for economic operators or persons who are active in multiple sectors, particularly multiple sectors of the same supply chain of these sectors.

- Furthermore, the overall text mass is quite huge. Finally, the updating is unnecessarily cumbersome where the provisions to be updated are basically the same or very similar.

12. Model B is similar to Model A except that users have to read two or more acts which reduces the main advantage of Model A. On the positive side, Model B avoids, within the scope of the reference, the downsides of Model A tremendously. For example it suffices, most of the time, to modify the lead act to implicitly change all the acts referring to it (provided that the normative references to the lead act are dynamic and that dynamic normative references are allowed in the respective jurisdiction). In cases, however, where the modification in the lead act is outside the scope of the normative reference whilst still being necessary, a new normative reference in the following acts might be needed as well. Furthermore, modifications in the lead act might not necessarily fit the following acts wherefore the normative references in the following acts might need to be limited or be subject to conditions. Finally, Model B can cause quite some damage across sectors where the lead act does not represent the best regulatory techniques.

13. With Model C, the regulator of the sector specific act still has the full control of the requirements because the requirements of the horizontal and semi-horizontal acts apply only as provided for in the sector specific act. This is important in particular where there are different regulatory competencies. At the same time, there is no unjustified duplication of text. Economic operators or persons are mostly exposed to identical requirements across sectors. If the horizontal and semi-horizontal acts really reflect the (generally) best regulatory techniques, Model C also ensures a high regulatory standard. The downside of Model C lies mostly in the regulatory management which becomes, as for Model B, cumbersome where the modification of the horizontal or semi-horizontal act does not fully fit to the act that normatively refers to them. Furthermore, users need to read several acts to have the full picture.

14. Model D is certainly the most easiest regulatory architecture to manage with minimum text and consistent requirements across sectors. It is logic and straightforward, as long as the horizontal and semi-horizontal acts do not, willingly or unwillingly, overrule sector specificities that merit being reflected. Due to the cross-sector applicability of horizontal or semi-horizontal acts, it is likely that sector specialists will protest where these acts fall behind the regulatory standard of the vertical acts. But this alone will not ensure that the horizontal and semi-horizontal acts reflect best regulatory techniques.

15. In summary, where the “to be established” requirements (and other provisions) are the same, or very similar across the various sectors, the more the choice should tend towards Model C or even Model D. Where there are more sector specificities, the more the choice should tend towards Model B or even Model A.

16. Under Model B and even more so under Models C and D, it should be ensured that the lead act (Model B) or the horizontal and semi-horizontal acts (Models C and D) reflect the best regulatory techniques. Sub-optimal regulatory techniques in the lead act or in horizontal and semi-horizontal acts brings the regulatory level down in large scale.

III. Combining these model architectures

17. Model A is logically exclusive to Models B, C, and D. But Models B, C, and D can be combined. For example it might make sense that for a certain horizontal aspect Act 1 applies by itself to all sectors, whereas Act 2 only applies to the extent that the vertical (sector) acts refer to it, because some sector specific adaptation needs to be made. It is even conceivable that an Act 3 applies semi-horizontally by itself to a large scale of sectors (Model D) and that other sectors / acts refer to parts of the same Act 3 according to Model C. An architecture using in this way Models C and D can still make use of Model B as well e.g. where only very few sectors have the same type of issue and this issue has been extremely well solved in one vertical Act 4. Why not let the other few vertical acts refer to the respective provisions of Act 4 instead of creating another semi-horizontal Act 5 for such a limited scope?

IV. Application of the same principles to different sections of one single act (intra-regulation architecture)

18. The analysis and the models described above with regard to entire acts can also be used with regard to the different sections and subsections of a single act. Amongst the sections, there are typically horizontal or semi-horizontal ones. But there can also be vertical sections or annexes that apply only to a part of the scope. Furthermore, it might be useful to follow Model B in some cases, namely where a few sub-sections or annexes have elements in common that do not merit a sub-section of higher order. Only Model A does not make sense in a single act.

V. Technical annexes

19. Another architectural question is: what to place into the annexes, what to place in the main part of the act? Evidently, there can be rules on this in each individual jurisdiction. To the extent that these rules do not prescribe one way or the other, the following considerations of regulatory architecture might help:

- Readers would expect the key elements of an act to be at least mentioned in the main part. If the key element is technically too complicated to be dispelled entirely in the main part, the main part can just mention it and refer to the annex. In some jurisdictions, it is even legally necessary to outline the key elements in the main part of the act.

- For readers, it is not necessarily easier to refer to an annex and then to come back to the initial place of reading. Thus it might be worthwhile checking whether the content of the annex is not short enough to be displayed in the main part of the act. But potential evolution should be taken into account. If the content is currently rather short but is likely to become longer, it is preferable to place it into an annex from the beginning.

- In particular, provisions, that are only relevant for some readers, generally speaking, are well placed in an annex. This is particularly the case if the act covers several different products, services of situations and each of them need specific vertical provisions. Here we come back to our Model D.

VI. Subordinate acts versus annexes

20. Annexes can compete with subordinate acts and vice-versa. Subject to the case, it is more efficient and user-friendly to cast technical content into an annex rather than into a subordinate act: the reader does not have to jump between two acts – everything is in one place.

21. However, sometimes the technical content is not yet ready when the main act is adopted or simply too complicated to be processed by parliamentarians / the legislator (e.g. test cycles for emission testing of vehicles). Hence it makes sense for the legislator to include just empowerment for the administration to adopt subordinate acts (regulation other than legislation) at a later point in time. Another reason for such a structure is that the technical content needs frequent updating, e.g. to technical progress. In this situation, the legislative procedure might be too slow or too cumbersome. The drawback of just empowering subordinate acts is that subordinate acts risk being incompatible with the main act or broader in scope than the main act. This can be legally problematic. Careful scrutiny is accordingly paramount.

22. An elegant compromise solution consists in placing the technical content into an annex, but to give the administration the empowerment to modify or even complement the annex. The annex thus becomes a hybrid text, partly (and in essence) adopted by the legislator and partly (namely for the details) adopted by the administration. This solution about regulatory architecture gives the legislator also the right to overrule, in a new legislative procedure, the content of amendments made by the administration in the meantime. In terms of democratic control, this is an advantage.

Conclusion

To conclude, when developing acts for a given sector or field it is important to consider how best to position an act in the overall regulatory architecture. Any prospective act should be consistent, efficient, based on best practices across various sectors, without redundancies, and user-friendly. This howtoregulate article examined four models of regulatory architecture, including the pros and cons of each model and when it might make sense to use one model over another. Some of the models may also be combined where it makes sense to do so. However, no one model is a panacea and so legislators need to be clear about the possible trade offs and red lines in order to ensure that the regulatory architecture will regulate the sector or field well, and that subsequent legislative actions can be made easily.