With many workplaces closed or closing, people working from home and the need for business transformation, there are calls for a “green recovery” in line with international climate change agreements to respond to global health, economic and trade shocks. One aspect of this sustainable transition is energy efficiency. This howtoregulate article analyses the best practice regulations jurisdictions use to encourage and incentivise energy efficiency. It builds on, and updates, a previous article written in January 2017, “Promoting energy efficiency by regulation” and so it is recommended both be read.

A. International Organisations and supra-national law

International Energy Agency (IEA)

1.The IEA is an autonomous inter-governmental organisation established in the framework of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) following the 1973 oil crisis. Although the IEA was initially focussed on energy in the form of oil it has broadened its focus to include renewables, gas and coal supply and demand, energy efficiency, clean energy technologies, electricity systems and markets, among others. The IEA works with policy makers to scale up action on energy efficiency to mitigate climate change, improve energy security and grow economies. As part of its energy efficiency programme it tracks global energy efficiency trends, energy efficiency indicators, and most important to us, a very useful list, including short summary, of global energy efficiency regulations.

International Standards Organisation (ISO)

2. ISO 50001 is the global energy management standard that some jurisdictions have regulated specific sectors adopt as part of their energy efficiency regulations (Taiwan, Mexico). The ISO is currently revising this standard after five years of service. The Technical Committee ISO/TC 301 Energy management and energy savings are responsible for the update. The ISO also covers energy standards for construction, renewable energy, IT and household appliances, transport, industrial products and processes, power generation, wind power and hydrogen.

3. For more information about how to include ISO standards in regulation please consult the howtoregulate article “Referring to standards: never think there is no further alternative”.

European Union (EU)

4. As foreshadowed in our 2017 howtoregulate article “Promoting energy efficiency by regulation”, the EU amended its Directive on Energy Efficiency (2018/2002) to update the policy framework to 2030 and beyond. Key elements of the amended directive include:

- a headline energy efficiency target for 2030 of at least 32.5%;

- EU countries will have to achieve new energy savings of 0.8% each year of final energy consumption for the 2021-2030 period, except Cyprus and Malta which will have to achieve 0.24% each year instead;

- stronger rules on metering and billing of thermal energy by giving consumers – especially those in multi-apartment building with collective heating systems – clearer rights to receive more frequent and more useful information on their energy consumption, also enabling them to better understand and control their heating bills;

- requiring Member States to have in place transparent, publicly available national rules on the allocation of the cost of heating, cooling and hot water consumption in multi-apartment and multi-purpose buildings with collective systems for such services;

- monitoring efficiency levels in new energy generation capacities;

- updated primary energy factor for electricity generation of 2.1 (down from the current 2.5); and

- a general review of the Energy Efficiency Directive (required by 2024), as a first step towards this review the EU published an assessment roadmap which closed for public comment on 21 September 2020.

5. The requirements for energy efficiency in buildings is covered under the amended Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EU)2018/844. The amended directive requires Member States to provide clear guidelines and outline measurable, targeted actions as well as promote equal access to financing, to achieve a highly energy efficient and decarbonised building stock and to transform existing buildings into nearly zero-energy buildings. The directive recognises that every 1% increase in energy savings from renovation of existing buildings reduces gas imports by 2.6%.

6. Following the December 2019 announcement of the European Green Deal, the EU increased its climate ambition and aims to become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. Ensuring buildings are more energy efficient will be regulated further as well as requirements for a cleaner construction sector.

American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE)

7. The ACEEE is a US non-profit organisation that produces an International Energy Efficient Scorecard every two years examining the efficiency policies, regulations and performance of 25 of the world’s top energy-consuming countries. The 2018 Scorecard listed the top ten jurisdictions with the most energy efficient policies and regulations as:

- Germany and Italy were tied for the top spot as they scored the same 75.5 / 100;

- France 73.5 / 100;

- UK;

- Japan;

- Spain;

- Netherlands;

- China;

- Taiwan;

- Canada and the USA tied at 10th position; and

- Mexico is the most improved country and ranked 12th.

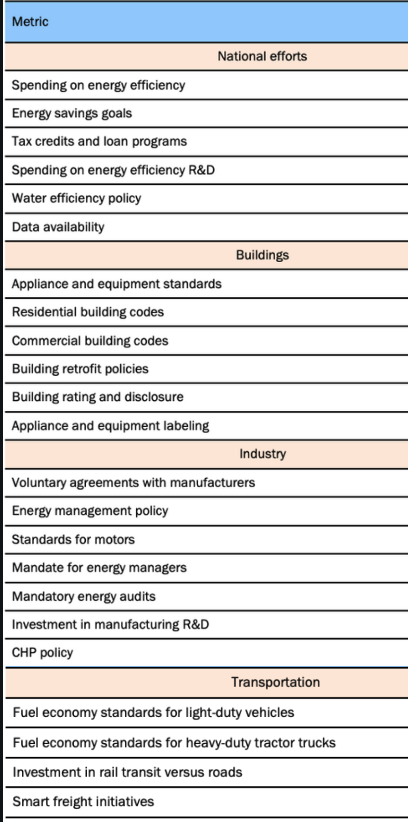

8. The metrics used by the ACEEE in developing the Scorecard are a useful reference for regulators seeking ideas about how to strengthen measures in energy efficiency regulations. The policy and regulatory metrics are organised as follows:

(Table reproduced from the 2018 Scorecard)1

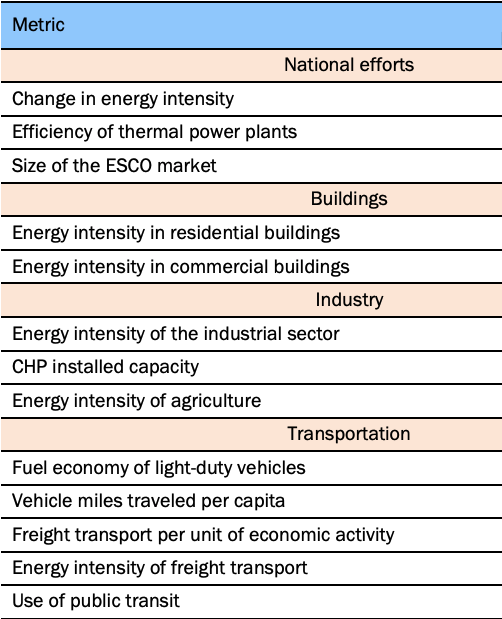

The performance metrics are organized as follows:

(Table reproduced from the 2018 Scorecard)2

B. National regulation

In developing this update on how to promote energy efficiency by regulation we decided to look at the energy efficiency regulation of jurisdictions that were considered to be effective using the ACEEE’s metrics. As the EU is an energy efficiency leader, many regulatory examples are European. China and Japan are also included as examples as they are energy efficient leaders in specific areas such as fuel efficiency standards. It is worth noting that India and Indonesia lead in some performance metrics around fuel efficiency but this was more reflective of the economic reality of household incomes than of any specific regulatory activity of the government or parliament.

Germany

1. Although Germany was required to develop a National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency as part of the EU’s Energy Efficiency Directive, it nonetheless has developed a comprehensive regulatory framework for energy efficiency. The Energy Conservation Act empowers the federal government to legislate ordinances for energy efficiency, including:

- to set up requirements concerning the thermal insulation of new buildings;

- in connection with the above mentioned basic obligation that new buildings will have to be “Nearly Zero Energy Buildings”, to set up requirements on the energy performance of these buildings;

- to set up requirements concerning design, selection and construction of systems or installations for heating, ventilation, cooling, lighting and hot water supply;

- to set up requirements concerning thermal insulation and technical appliances in case of buildings undergoing major renovations, and – under certain preconditions – to foresee specific requirements for buildings and appliances not subject to any other changes;

- to set up requirements concerning the operation of systems and installations for heating, ventilation, cooling, lighting and hot water supply;

- to set up requirements on the determination and distribution of costs of collective heating or ventilation systems or systems for collective supply of hot water;

- to define content and use of energy certificates based on energy demand and metered energy; and

- to set up general requirements on the control of energy certificates and inspection reports.

2. The Energy Conservation Ordinance (EnEV) outlines additional requirements for energy efficiency:

- since January 2016 new buildings require a reduction of approximately 25% in primary energy consumption and around 20% heat transfer loss;

- existing buildings have requirements for replacement of shop windows and external doors;

- obligation to disclose key energy figures in real estate advertisements when selling and renting properties;

- obligation to provide energy performance certificate to a potential buyer or tenant at the viewing stage;

- duty to display energy performance certificates in buildings used by public authorities and frequently visited by the public;

- obligation to display energy performance certificates in certain buildings which are frequently visited by the public, but which are not occupied by public authorities;

- Introduction of an independent system for spot checks of energy performance certificates and reports on the inspection of air conditioning systems;

- Obligation to decommission constant temperature boilers installed before 1 January 1985 or which have been in service for more than 30 years; and

- Non-compliance with the above incurs a fine.3

3. Germany’s Renewable Energies Heat Act requires new buildings to use renewable energies and for public sector buildings, renewable energy must also be used for major renovations.

4. The Heating Cost Ordinance encourages energy users to conserve energy by requiring the allocation of costs for heating and hot water production in centrally supplied buildings with two or more units to be billed based on consumption. It also regulates the obligation to carry out metering as well as the fitting of technical equipment for metering. An exemption from the obligation to carry out metering also acts as an incentive to attain the passive house standard in the construction of new buildings or the refurbishment of multiple-family dwellings.

Italy

5. The jewel in the crown of Italy’s energy efficiency regulatory framework is its “White Certificate” Trading Scheme established under Decree July, 20th 2004 (Autorità per l’energia elettrica e il gas). White certificates are tradable instruments giving proof of the achievement of end-use energy savings through energy efficiency improvement initiatives and projects. It is a market-based scheme where regulations define the categories of the projects and the regulated subjects, and the market selects the technologies and sectors. Electricity and natural gas distributors (and their controlled companies) with more than 50,000 customers are required to achieve annual quantitive primary energy saving targets, expressed in Tonnes of Oil Equivalent saved. Only the additional savings over and above spontaneous market trends and/or legislative requirements are considered. Other parties eligible to submit projects (on a voluntary basis) for accruing white certificates include:

- non-obliged distributors;

- companies operating in the sector of energy services (ESCOs); and

- companies or organisations having an energy manager or an ISO 50001 certified energy management system in place.

GSE is the energy services operator, it is a state owned enterprise under the responsibility of the Ministry of Economy and Finance and are responsible for verifying and issuing the white certificates. For more detailed information about the scheme see here.

6. Since January 2018 Italy requires non-residential buildings over 500m2 or residential building with 10 adjoined units to receive a building permit if the project includes charging infrastructure for electronic vehicles. This also applies to buildings seeking a permit for major renovations. The relevant legislative decree is 16/12/2016 no. 257, which transposes EU directive 2014/94/EU.

France

7. Law no. 2015-992 on the Energy Transition for Green Growth Act (English or French) outlines France’s energy efficiency ambition for buildings and homes and for transport among many other goals for green growth and lowering energy consumption. The following measures aim to encourage more energy efficient buildings and homes:

- An energy transition tax credit is applicable for up to 30% of the cost of works, up to a limit of €8,000 of works for a single person and €16,000 for a couple.

- An interest-free loan can be used for financing energy refurbishment works.

- Energy refurbishment help centres provide information and advice to individuals on their renewal works.

- Requiring energy refurbishment works when renovating a facade, re-roofing or undertaking a loft conversion.4

8. France’s regulatory measures to make transport energy efficient was noted as best practice in ACEEE’s 2018 Scorecard and includes:

- Incentives for the purchasing of clean vehicles by individuals (the €10,000 electric car bonus has been in place since 1 April 2015, to replace an old, polluting diesel vehicle), by the State (50% of fleet renewals with low-emissions vehicles), by local authorities (20%) of buses and coaches (100% of these will be low-emissions vehicles by 2025) and vehicle hire companies, taxis and chauffeured vehicles (10% of replaced vehicles will be low-emissions vehicles).

- Business mobility plans promoting car-pooling between employees.

- Incentivising commuting by bike and tax breaks for businesses.

- An energy transition tax credit to finance the installation in homes of electric vehicle recharging points.5

9. France’s energy efficiency by regulation tax credits are regulated in the annual law of finance. For example the tax credit for energy efficient housing expenditures and renewable energy investment “Crédit d’Impôt pour la Transition Énergétique” (CITE), was amended for application in tax year 2020 under Law no. 2019-1479 Section 15. Section 15 contains useful tables outlining the expense and the tax credit households can expect if they meet the income conditions (wealthy households are not eligible for the tax credit). Further information (French) about CITE can be found here. An evaluation of the CITE programme found:

The CITE reduces energy consumption and CO2 emissions respectively by about 0.9 TWh and 0.12 MtCO2 per year in 2015 and 2016. These effects last for several years: over the 2015-2050 period, 2.9 MtCO2 and 43 TWh of energy consumption are avoided when the CITE is removed in 2017. The cumulative gain of CO2 emissions over 2015-2050 triggered by additional 2015 investments corresponds to 7% of the 2015 level of CO2 emissions of the housing sector.

Mexico

10. Mexico’s Energy Transition Law outlines a training/coaching approach to promote the adoption of energy efficient management systems (PRONASGEn). PRONASGEn promotes the improvement of energy performance among energy users through the implementation of energy management systems (such as ISO 50001, also adopted as the national standard NMX-J-SSA-50001-ANCE-IMNC-2019), establishing technical and management measures to raise competitiveness. Although PRONASGEn is voluntary, it targets large energy users, more recently small to medium-sized enterprises, refineries and public buildings have also been included in the learning networks. Via an online platform participants support each other by sharing experiences, supported by national and international experts.

Japan

11. Japan’s regulatory approach to energy efficiency mostly focusses on incentives such as voluntary actions, financial incentives (loan schemes, tax credits) to encourage energy efficiencies in the industrial sector. In late 2018 Japan revised its Act on the Rational Use of Energy (see howtoregulaten article “Promoting energy efficiency by regulation” for the Act’s background). The key revisions include requirements to improve on energy efficiency results, permission for group company reporting system and a new definition for “consigners”.

12. Under the Rational Use of Energy Act Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) are empowered to set fuel efficiency standards for trucks and buses. In 2019 METI updated the the standard requiring manufacturers to enhance the fuel efficiency by approximately 13.4% for trucks and other heavy vehicles and by approximately 14.3% for buses setting 2025 as the target year and 2015 as the base year. Japan is one of a handful of jurisdictions that has a fuel economy programme for heavy vehicles

China

13. China is also one of the handful of jurisdictions that have fuel economy programmes for heavy vehicles, and like Japan it also updated its standard in 2019 (Fuel consumption limits for heavy-duty commercial vehicles GB 30510-2018). The recently updated standards require vendors of heavy vehicles to comply with the fuel consumption values listed for the following vehicles:

- Straight trucks;

- Tractor-trailers;

- Coaches;

- Dump trucks; and

- City buses.

Conformity with the standard shall be measured according to GB/T27840-2011, and the deviation between the measurement result and the type approval value shall not exceed 6% (paragraph 6 of GB 30510-2018). China is the world’s largest market for heavy-duty commercial vehicles and this updated regulatory standard would have meaningful impact. China is also the world’s largest electric vehicle market and the state owned enterprise, Shenzhen Bus Company is the first bus and taxi company to electrify its fleet: 6,053 buses, 4,681 taxis, 104 charging station with 1,700 electric bus chargers and 980 electric taxi chargers6.

C. Noteworthy regulatory actions

1. Singapore is aiming for all light bulbs sold in Singapore to be minimally as energy efficient as LED bulbs from 2023 onwards. The Energy Conservation Act empowers the Singapore National Environmental Agency (NEA) to make regulatory improvements to standards. As part of initiative the the Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) of lamps will be raised to facilitate the phase out of halogen bulbs and accelerate the switch among consumers to using more energy efficient lamps. NEA will also be introducing MEPS for fluorescent lamp ballasts. The NEA regulatory update includes a useful graphic about the energy efficiencies between the different light bulbs, reproduced below and also a summary of the regulatory changes (not reproduced), which represents a commendable effort to communicate their regulatory activity.

2. New Zealand uses data from its Productivity Commission to inform their regulatory ambition to develop a fuel efficiency standard for light vehicles. Noting that “[t]ransport accounts for 20% of domestic greenhouse gas emissions, and is New Zealand’s fastest growing source of emissions. Between 1990 and 2017, gross emissions across the economy grew by 23% with transport emissions growing by 82%, and road emissions increasing by 93%…[w]ithout additional policy intervention emissions for light vehicles are projected to grow”7. Although the regulation is in the drafting stage New Zealand intends to regulate light vehicle fuel efficiency standards and rebate scheme for purchasing low emission vehicles to incentivise consumers. A fuel efficient standard for heavy vehicles will be the subject of future regulation.

3. From 2021 all air conditioners and refrigerators in Rwanda are required to meet the newly regulated MEPS for such products. The MEPS applies to ductless split air conditioners and self-contained air conditioners, refrigerators, refrigerator-freezers and freezers. Rwanda’s regulatory framework regulates:

-

requirements for air conditioners and their refrigerants (paragraph 2.2.1.1);

-

the energy-efficient requirements (paragraph 2.2.1.2);

-

the scope of covered products (paragraph 2.2.1.4);

- exemptions (paragraph 2.2.1.5);

- maximum energy use requirements (paragraph 2.2.1.6);

- labelling requirements (paragraphs 2.2.1.7 and 2.2.1.11);

- compliance certification, surveillance testing and conformity (Annex 3); and

- a benchmark for models representing the highest-efficiency products in major markets (Annex 4).

D. Opportunities to strengthen energy efficiency regulation

1. Where legislators are not always very sure about which measures they should take to promote energy efficiency by regulation, opportunities could be found by making programmes more precise by gathering more information. For example regulation can be used to push for a deeper analysis of a policy problem that might be the subject of a more specific regulation further down the track. Such call for a deeper analysis was introduced (but did not get passed into law) in the US House of Representatives the AI Jobs Act, the aim of which was to promote a “21st century artificial intelligence workforce”. The AI Jobs Act Bill required the Secretary of Labor, in collaboration with others outlined in the bill, to prepare and submit to the relevant House of Representative Committee, a report on AI and its impact on the workforce. The bill outlined specific matters the Secretary of Labour would need to include in the report, see paragraph 4 of howtoregulate article “Report on AI: Part I – the existing regulatory landscape” for more detail. To oblige the authorities to develop a report is thus the absolute minimum whenever the legislator does not know what to do precisely, as seems to be the case for quite some legislators in that field.

2. The obligation to draft a report can be further enhanced by the obligation to compare best methods in various geographic entities within the jurisdiction in question or in other jurisdictions. Preferably, the legislator should, in case of uncertainty, oblige the administration to develop also a concrete plan and to describe the means necessary for its implementation. The legislator can oblige the administration to immediately come back to the legislator with the plan or to do so after a certain period of implementation time, which is often a more useful approach.

3. Once there is an agreed plan, it must be operationalised. Any operationalisation of an energy efficiency plan or policy requires that the legislator creates the necessary collateral measures and/or that the correct government bodies have the empowerments to implement a plan, whilst quite some plans or even regulation is lacking such empowerments or collateral measures and thus are not fully promising. For example the UK announced that gas boilers would be replaced by low-carbon heating systems in all new houses built after 2025. Such a policy announcement would require a change in the building regulations to prohibit installation of gas boilers or the empowerment for the authorities to impose low-carbon heating systems. There has not yet been regulatory action to update the UK’s building regulations and so it is difficult to see how this policy will become a reality.

4. For a detailed catalogue of empowerments see the two articles: “Empowerments (Part I): typology” and “Empowerments (Part II): The empowerment checklist”. With the right empowerments, the relevant government body may be able to enact delegated regulation in the form of standards or rules, impose obligations on actors, which are underpinned by sanctions, and foresee concrete verification measures, if needed including third parties. But with the right empowerments, the relevant government body might also create incentives to make actors move further towards energy efficiency by regulation than legally required. Means to that end include quality labels, public praise, advantages in public tenders, waivers from periodic emissions inspection obligations, longer validity of certificates and other indirect financial incentives such as lower insurance rates or privileged access to subsidies or grants. Comprehensive empowering of the administration is ever more important in so far as technical standards and requirements must be often adapted to technical progress. Regarding the various possibilities of adaptation to technical progress, see Section 3.12 of the Handbook “How to regulate?”.

E. Conclusion

Promoting energy efficiency by regulation is important to foster the necessary market conditions and steer consumer behaviour towards making climate change obligations a reality. The examples contained in this howtoregulate update covered buildings, transport and industry, citing regulatory techniques such setting clear requirements and standards, tax credits, training and education approaches and market-based schemes. No one regulatory action is a silver bullet and so a suite of regulatory actions are necessary to create the right conditions for an energy efficient life.

This article was written by Valerie Thomas, on behalf of the Regulatory Institute, Brussels and Lisbon.

1 Castro-Alvarez et al, The 2018 International Energy Efficiency Scorecard, Report I1801, June 2018, pp. 16-17.

3 German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/EN/Artikel/Energy/energy-conservation-legislation.html.

4 https://www.gouvernement.fr/en/energy-transition#:~:text=and%20energy%20efficiency.-,The%20Act%20of%2017%20August%202015%20on%20energy%20transition%20for,order%20to%20boost%20green%20growth..

6 https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190625005489/en/Shenzhen-Bus-Group-Honoured-Outstanding-Achievement-Green.

7 New Zealand Ministry of Transport, Low Emission Vehicles Regulatory Impact Statement, 2019/06/27, p. 1, https://www.transport.govt.nz/multi-modal/climatechange/electric-vehicles/clean-cars/.