Governments are increasingly looking towards automated decision-making systems (ADS), including algorithms to improve the delivery of public administration. This raises issues in administrative law around legality, transparency, accountability, procedural fairness and natural justice. The provision of public services and government decision-making are regulated by legislation that protect administrative (public) law principles and permit affected persons to seek judicial review of that decision. However, the government use and deployment of ADS has, in many jurisdictions, preceded any prudent analysis of how the ADS fits within the broader administrative legal framework. This howtoregulate article outlines a regulatory framework for the automation of public administration.

A. Questions of substance for regulating the government use of ADS

1. We focus this howtoregulate article on the government use of ADS in public administration (either delivering public services or decision-making) because of the implications to an individual’s legal rights, such as granting a social security benefit. In the private sphere, a bank not granting credit to an individual, while not affecting a legal right to credit per se, may nonetheless have the same effect on that individual’s welfare as not granting a social security benefit. However, public administration is a special situation where the individual does not have choice in service delivery in the same way as choice is offered in the private sphere. Therefore, it merits particular care and attention. ADS use in the judicial sector also merits attention but is outside of the scope of this howtoregulate article.

Identifying the policy goals for automating public administration

2. Many jurisdictions have identified digital government, e-government and automation of public administration as important policy goals of the modern state. This is evidenced by the number of states that have developed digital strategies and the investment they have put into supporting digital infrastructure. The Handbook: How to regulate? discusses the value of identifying the “goals behind the goals” as a means for determining appropriate regulatory measures:

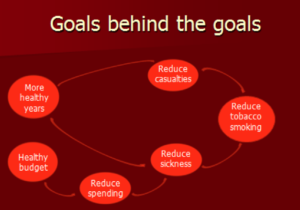

“Some of the “goals behind the goals” build chains. The goals which do not depend on other goals, at the end of the chains, shall be called primary goals…goals which are between the primary goals and the officially set goals shall be called intermediate goals.”1

The below illustration from the Handbook, using the example of the policy goal to reduce tobacco smoking, shows that other goals could include: to reduce casualties and to reduce illness. These two goals could be intermediate. For example behind the intermediate goal to reduce sickness another intermediate goal could be identified: to reduce spending and to reduce spending in the health budget.

3. Taking a look now at the policy goal to automate public administration we can see that automation is itself an intermediate goal to the primary goal of an efficient and effective public administration system:

- efficiency: reduce public spending of manual public administration;

- efficiency: recover debt from incorrect beneficiaries;

- effectiveness: target the correct beneficiary of the legislation;

- effectiveness: no delays to beneficiary receiving decision, service or funding; and

- rule of law: enhance compliance with legislation by reducing human errors or inconsistency.

We should keep this primary goal in mind when developing ADS regulation, and thus also in the following.

4. But it is not the only one. In October 2019 the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights reported (A/74/493) to the 74th session of the General Assembly that:

“The digital welfare state is either already a reality or emerging in many countries across the globe…systems of social protection and assistance are increasingly driven by digital data and technologies that are used to automate, predict, identify, surveil, detect, target and punish…the irresistible attractions for Governments to move in this direction are acknowledged, but the grave risk of stumbling, zombie-like, into a digital welfare dystopia is highlighted. It is argued that big technology companies (frequently referred to as “big tech”) operate in an almost human rights-free zone, and that this is especially problematic when the private sector is taking a leading role in designing, constructing and even operating significant parts of the digital welfare state. It is recommended in the report that, instead of obsessing about fraud, cost savings, sanctions, and market-driven definitions of efficiency, the starting point should be on how welfare budgets could be transformed through technology to ensure a higher standard of living for the vulnerable and disadvantaged.”2

In investigating the human rights issues around digital government the UN suggests that the policy goal should not be automating public administration. Instead, the UN advocates, the policy goal should be “higher standard of living for the vulnerable and disadvantaged” and automation is the intermediate goal or even just an objective.

5. Administrative (public) law principles also govern such policy goals and so worthwhile objectives should include:

- transparency: clear reasons provided for the decision, service or funding;

- accountability: who or how the process for deciding, service delivery or funding was determined;

- scope: the extent to which an ADS was used and the role of the human decision-maker;

- compliance: enhance the legislative basis of the public administrative act;

- accessibility: those that cannot access the digital system have appropriate alternatives for accessing public administration; and

- fairness: situations of a similar nature are treated the same.

Clear goals and objectives help drive good design of ADS in public administration but are insufficient on their own. Regulating the automation of public administration needs to have robust measures that test the extent to which the goals and objectives have been met, including how any potential conflicts between goals are resolved. The examples of governments abandoning deployed ADS (eg. “Robodebt”) due to contravention of either legislation or administrative law generally, suggest the above objectives make for good regulatory requirements to ensure legitimacy in ADS design. Hence we strongly recommend establishing a map of primary goals, intermediate goals and objectives before even designing ADS regulation.

6. ADS regulation requires further decisions on a range of aspects or parameters. We list them in the following, together with a few generic recommendations:

-

Deciding which public administrative acts to automate

7. Irrespective of how sophisticated the technology has progressed there may be decisions that would not be appropriate to remove the human decision-maker from the process. For example some legislation permits discretion to be used either by the minister or senior public servant and it is suggested that this is not an appropriate administrative act to automate.3 It may be useful for any regulation of the automation of public administrative acts to consider which acts should be prohibited from automating. The success and in particular the acceptance of ADS depends on avoiding evident or frequent mistakes – mistake tolerance might even be lower than for human decisions. This objective can only be reached by properly limiting the scope of ADS to aspects and situations where it is very well performing.

-

Requiring impact assessments

8. By requiring impact assessments to decide which public administrative acts to automate is a useful exercise to determine the appropriateness of automation or the degree to which automation may be useful. The benefit of requiring an impact assessment before design is that it scrutinises the rationale that automation is more efficient because it “saves time and money”. However, such an assessment may be based on a short term understanding of costs. The illustrative case of Robodebt highlights how an automated system that initially saved money in recovering overpayments of welfare benefits turned out to be more expensive because its design was based on flawed rules found to be unlawful. Although some jurisdictions require impact assessment as part of the design phase, we suggest this may be too late in the process as the decision to automate has already been made.

-

Expert systems

9. The Australian Administrative Review Council published a report “Automated Assistance in Administrative Decision Making 2004”, which outlined five principles about the suitability of expert systems for administrative decision-making:

- Principle 1 – Expert systems that make a decision—as opposed to helping a decision maker make a decision—would generally be suitable only for decisions involving non- discretionary elements.

- Principle 2 – Expert systems should not automate the exercise of discretion.

- Principle 3 – Expert systems can be used as an administrative tool to assist an officer in exercising his or her discretion. In these cases the systems should be designed so that they do not fetter the decision maker in the exercise of his or her power by recommending or guiding the decision maker to a particular outcome.

- Principle 4 – Any information provided by an expert system to assist a decision maker in exercising discretion must accurately reflect relevant government law and policy.

- Principle 5 – The use of an expert system to make a decision—as opposed to helping a decision maker make a decision—should be legislatively sanctioned to ensure that it is compatible with the legal principles of authorised decision making.

The principles outlined above consider the degree to which automation is used in the decision-making process. Regulation could include requirements around the degree to which an ADS may be used and the circumstances. For example particular “final” decisions should be made by a human and not an ADS. In circumstances where a human is to make the final decision, it may be appropriate to outline a series of tests the human should make in understanding the information and analysis provided by the ADS.

-

Learning from pioneering sectors

10. ADS is much older than (today’s) artificial intelligence. ADS has been used in some national tax administrations (both for income tax and value added tax) in the eighties already. Most of the issues of ADS are not artificial intelligence specific. Hence, it might make sense to study the pioneer sectors, their difficulties and how they overcame the difficulties. It might also make sense for officials to tap into the knowledge of their colleagues from these pioneering sectors, the more so as quite some legal and practical issues might be specific to the respective jurisdiction.

-

Applying project and/or change management

11. The introduction of ADS is mostly a complicated undertaking which merits being planned carefully, meaning applying principles of project management, change management or even both. We assume that a part of the failure stories could have been avoided by better management.

-

Adapting regulation to ADS needs

12. There might be room for reaching better ADS results by adapting regulation to ADS needs, namely by using an ADS-friendly language that avoids ambiguities. We cannot assess, however, whether adapting regulation to ADS is on average worthwhile or not. We suppose that it depends on the case and that the utility of such adaptation will decrease over time. If interested in this path, readers might obtain good results by using the search terms “machine-readable laws”.

B. International

I. United Nations (UN)

1. The UN Committee of Experts on Public Administration (CEPA) was established by resolution 2001/45 of the Economic and Social Council to ensure the promotion and development of public administration and governance among Member States. The CEPA meet annually and provide guidelines on public administration issues related to the implementation of goals: IADGs and SDGs. Goals that touch on ADS in public administration, include:

- E-government for improved transparency and public service delivery.

- Role of the public sector in advancing the knowledge society: Member states should “Perceive the national public administrations as e-governments, that produce and seek knowledge in order to use it to deliver public value to the citizens”.

- Serving the information age.

2. The UN e-government digital index (EGDI) is a survey with 11 iterations that ranks 193 UN Member States in terms of digital government – capturing the scope and quality of online services, status of telecommunication infrastructure and existing human capacity. The 2020 ranking is led by Denmark, the Republic of Korea, and Estonia, followed by Finland, Australia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, the United States of America, the Netherlands, Singapore, Iceland, Norway and Japan. The key takeaways for ADS use in public administration from the 2020 EGDI, include:

-

Before starting any automation process institutions and organisations need to be reorganised to establish appropriate horizontal and vertical workflows.4

-

Organisational culture in the public service is important to foster collaboration and innovation within public administration.5 Public servants need to have the capacity to work across different government departments and with other State institutions, and they need to be able to raise public awareness and involve civil society and other stakeholders in governance processes. New attitudes, skills and behaviours are needed for interaction with vulnerable groups and to engage individuals and administrators at various levels of government in the localisation of the SDGs.6

-

In engaging personnel for digital government transformation, excessive reliance on vendors or private sector expertise should be avoided, as the Government might lack the capacity to follow up on problems that arise in the implementation phase. Although international cooperation and support are desirable and often necessary, skills and knowledge should be locally sourced whenever possible. It is crucial to secure a high ratio of IT specialists to other types of expertise in government and to take on quality personnel.7

-

In developing a comprehensive institutional and regulatory framework that allows countries to deliver digital services in a convenient, reliable, secure and personalised manner, it is necessary to take stock of what laws and regulations exist and how they are interrelated in order to identify gaps and establish a point of departure for the adoption and harmonisation of legislation fully supportive of digital government transformation.

-

When developing legislation, regulations and strategies for digital government transformation, it is essential to take the needs of vulnerable groups into account from the start, with emphasis given to safety, availability, affordability and access to services.

-

A thorough understanding of the potential positive and negative effects of existing policies on the use of new and emerging technologies (such as AI) and a comprehensive understanding of the technologies themselves are necessary to formulate relevant new laws and policies. Partnerships among public and private sector actors, universities and think tanks can help build the necessary understanding of the impacts of new technologies, how they can benefit societies, the risks they pose in terms of safety and security, and the ethical issues that must be addressed in their design and use.8

-

Trust in government is integral to the success of government digital transformation. Governments need to show that they are credible in terms of providing safe and consistent access to services, promoting digital literacy, and enabling the participation of all groups in society, particularly the most vulnerable.9

-

Older persons must be given careful consideration in the design of public service delivery models and the provision of government services. The lack of convenient access to social services through online portals or service centres can reinforce their exclusion and keep them on the wrong side of the digital divide. Governments need to identify and address the specific challenges faced by older persons so that no one is left behind.10

-

Since digital government is a journey and not a final destination, the continuous monitoring and evaluation of digital services is essential. Performance indicators can comprise both quantitative and qualitative measures that assess variables such as user uptake, user satisfaction, and the share of automated customer service generated by the digital government system. Where applicable and possible, data should be disaggregated by gender, age, disability status, setting (urban/rural), and other relevant factors to analyse outcomes for different demographic groups. Some countries have adopted a digital government implementation index to establish benchmarks for public institutions and monitor progress.11

II. OECD

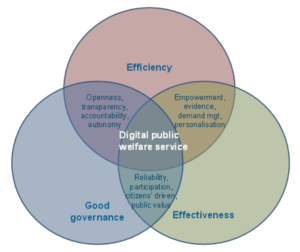

3. In July 2014, the OECD Council adopted the Recommendation that the governments of OECD member countries develop and implement digital government strategies to assist and guide digital transformation. The basis of the Recommendation is that digital technologies contribute to:

- create open, participatory and trustworthy public sectors;

- improve social inclusiveness and government accountability; and

- bring together government and non-government actors to develop innovative approaches to contribute to national development and long-term sustainable growth.

The Recommendation, which is the first international legal instrument on digital government, offers a whole-of-government approach that addresses the potential cross-cutting role of digital technologies in the design and implementation of public policies, and in achieving policy outcomes.12 The objective of the Recommendation is to achieve a progression from “digitisation”, through “e-government” to “Digital Government”. The principles outlined in the Recommendation for capturing the value of digital technologies for more open, participatory and innovative governments, include:

- Using technology to improve government accountability, social inclusiveness and partnerships.

- Creating a data-driven culture in the public sector.

- Ensuring coherent use of digital technologies across policy areas and levels of government.

- Strengthen the ties between digital government and broader public governance agendas.

- Reflecting a risk management approach to address digital security and privacy issues.

- Developing clear business cases to sustain the funding and success of digital technologies projects.

- Reinforcing institutional capacities to manage and monitor project implementation.

- Assessing existing assets to guide procurement of digital technologies.

- Reviewing legal and regulatory frameworks to allow digital opportunities to be seized.

4. The OECD have developed a Going Digital Toolkit, which helps countries assess their state of digital development and formulate policy strategies and approaches in response. The Toolkit is structured along the 7 policy dimensions of the Going Digital Integrated Policy Framework: access; use; innovation; jobs; society; trust; market openness; and growth and well-being.

III. European Union (EU)

5. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has provisions regulating the use by governments of Member States of:

- automated decision-making (without human involvement), and

- profiling (automated processing of personal data to evaluate certain things about an individual, which may form part of an automated decision-making process).

Article 22 of the GDPR permits a decision solely by automated means without human involvement only where the decision is:

- necessary for the entry into or performance of a contract; or

- authorised by EU or Member State law applicable to the controller; or

- based on the individual’s explicit consent.

Additional Article 22 rules protect individuals where automated decision-making has legal or similar significant effect, where such decision-making occurs, the Member State must ensure that:

- individuals are given information about the processing of automated decision-making;

- simple mechanisms are introduced for individuals to request human intervention or challenge a decision; and

- regular checks are carried out to make sure that ADS systems are working as intended.

Article 35 requires an impact assessment to be completed “[w]here a type of processing in particular using new technologies, and taking into account the nature, scope, context and purposes of the processing, is likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons ”. Article 35(7)] outlines the minimum criteria that the impact assessment must consider and assess, such as describing the processing operations, assessing the necessity and proportionality etc.

6. Article 51 of the GDPR requires the creation of “one or more independent public authorities to be responsible for monitoring the application of [the GDPR], in order to protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons in relation to processing and to facilitate the free flow of personal data within the Union”. Article 52 requires the supervisory authority to act with independence in completing its tasks and exercising its powers. Specific characteristics of independence is characterised as:

- Article 52(2) – free from external influence, whether direct or indirect, and shall neither seek nor take instructions from anybody;

- Article 52(3) – member(s) of each supervisory authority shall refrain from any action incompatible with their duties and shall not, during their term of office, engage in any incompatible occupation, whether gainful or not;

- Article 52(4) – each supervisory authority is provided with the human, technical and financial resources, premises and infrastructure necessary for the effective performance of its tasks and exercise of its powers;

- Article 52(5) – each supervisory authority chooses and has its own staff which shall be subject to the exclusive direction of the member or members of the supervisory authority concerned; and

- Article 52(6) – ensure that each supervisory authority is subject to financial control which does not affect its independence and that it has separate, public annual budgets, which may be part of the overall state or national budget.

C. National legislation

To the best of our knowledge there exists no comprehensive, cross-sector primary legislation regulating the government’s use of ADS specifically (we do not count here sector specific rules, e.g. embedded in tax regulations). Nevertheless, some jurisdictions seek to regulate ADS use via directives, principles and policies, some of which carry non-compliance measures from the primary legislation eg. Canada. We start our analysis with legislation that regulates particular aspects of ADS use.

I. Legislative safeguards regulating automated decision-making

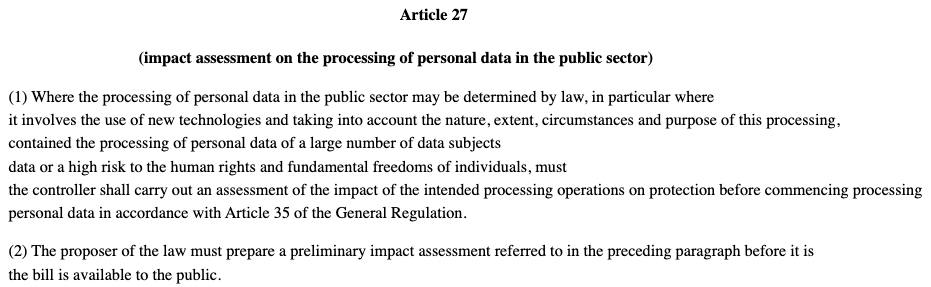

1. Unsurprisingly, the EU Member States that transposed Article 22 of the GDPR regarding automated decision-making and profiling did provide legislative safeguards for ADS. Perhaps the most stringent protection is that proposed by Slovenia’s Law on Protection of Personal Data (ZVOP-2), which transposes the GDPR. Using online translation from Slovenian to English, Article 27 states:

Article 27 is unique as it proposes an ex ante safeguard where a bill relating to public sector processing of data involving the use of new technologies must include a completed impact assessment on human rights and fundamental freedoms of individuals. This suggests that should the impact assessment show a disproportionate infringement on human rights and fundamental rights, the bill will not be passed into law.

2. The next level of protection is ex post in that where an automated decision, duly authorised by law is made, the following safeguards aim to protect the rights of individuals affected by such decisions [UK Data Protection Act 2018 (Section 14) and Ireland Data Protection Act 2018 (Section 57)]:

-

notification to the individual (data subject) that a decision has been based solely on automated processing;

-

request (within a time limit following notification) for the decision to be reviewed or request a new decision not based solely on automated processing; and

- where a request has been made the decision-maker (data controller) must: (a) “consider the request, including any information provided by the data subject that is relevant to it, (b) comply with the request, and (c) by notice in writing inform the data subject of: (i) the steps taken to comply with the request, and (ii) the outcome of complying with the request”.

Both the UK and Ireland Data Protection Acts require an impact assessment before the processing of personal data operations, but not before the law permitting such processing of personal data, is enacted.

3. France’s Law Relating to Protection of Personal Data (Loi n°2018-493 du 20 juin 2018) regulates directly automated decisions made in the:

-

judiciary, prohibition semi or fully automated decision if such processing is intended to evaluate aspects of personality;

-

public administration, recognises differences between semi-automated decisions and fully automated decisions. Fully automated decisions are prevented in actions brought to the administrative court and other kinds of administrative decisions are permitted (either semi-automated or fully automated) under specific conditions where:

-

it does not involve sensitive data;

-

it respects Chapter I of Title I of Book IV of the Code of Relations between the Public and Administration.

-

it respects Article L. 311-3-1 of the Code of Relations between the Public and Administration, whereby a decision taken on the basis of algorithmic processing shall include an explicit notification informing the individual concerned

-

the administration communicates the rules defining this data processing and the main characteristics of its implementation to the individual upon request;

-

the data controller ensures the control of the algorithmic processing and its developments in order to be able to explain, in detail and in an intelligible form, to the individual concerned how the processing has been implemented in his or her individual case;

-

-

all other kinds of automated decisions that have a legal effect.

4. Australia’s Migration Act 1958, Section 495A specifically permits the use of “computer programmes” to assist in the decision-making of migration law and that accountability for that decision rests with the Minister. The Migration Act also permits the Minister to substitute a more favourable decision (than that made by the “computer programme”) to the applicant and lists the condition for this to occur (Section 495B). The Explanatory Memorandum to the bill that amended the Migration Act making Section 495A law noted that it foresees the use of computer programmes in:

“8. … making decisions on certain visa applications where the criteria for grant are simple and objective. There is no intention for complex decisions, requiring any assessment of discretionary criteria, to be made by computer programmes. Those complex decisions will continue to be made by persons who are delegates of the Minister.

9. To illustrate this, it may never be appropriate for computer programmes to make decisions on visa cancellations. Computer-based processing is not suitable in these circumstances because these decisions require an assessment of discretionary factors which do not lend themselves to automated assessment.”

II. Regulations for ADS subject to legislation

5. Canada’s Directive on Automated Decision-making is issued under the authority of Section 7 of the Financial Administration Act (FDA). The consequences of non-compliance can include any measure allowed by the FDA that the Treasury Board would determine as appropriate and acceptable. This Directive is perhaps the most comprehensive regulation on automated decision-making in public administration and reflects the Government of Canada’s plan to use artificial intelligence to make, or assist in making, administrative decisions to improve service delivery. Government’s commitment to digital transformation must be compatible with core administrative law principles such as transparency, accountability, legality, and procedural fairness. Understanding that this technology is changing rapidly, the Directive is intended to be a “living document” that evolves to ensure it remains relevant.

6. The Directive commenced on 1 April 2020 and will be automatically reviewed every 6 months. It applies to any ADS developed or procured after 1 April 2020. It is not retroactive and so any ADS already in use is not within the Directive’s scope and excludes ADS in a testing environment. The objective of the Directive is to ensure that “client service experience and government operations are improved through digital transformation approaches”. It is expected that government results of this Directive include:

- integrated decision-making is supported by enterprise governance, planning and reporting;

- service delivery, business and program innovation are enabled by technology and data;

- service design and delivery of ADS is client-centric by design; and

- workforce capacity and capability development is supported.

Each of these four expected results have requirements for different government agencies and outlines the responsibilities of senior public servants, Deputy Heads, as follows:

- strategic IT management, such as ensuring departmental operations are digitally enabled;

- ensuring that ADS is responsible and ethically used, in accordance with Treasury Board direction and guidance, including that decisions produced by the ADS are efficient, accountable and unbiased;

- open access to digital tools;

- ensuring that the network and devices used are monitored and used appropriately;

- cyber security and identity, clearly identifying and establishing departmental roles and responsibilities for reporting cyber security events and incidents, including events that result in a privacy breach, in accordance with the direction for the management of cyber security events from the Chief Information Officer of Canada;

- monitoring and oversight.

7. The Framework for the Management of Compliance (Appendix C: Consequences for Institutions and Appendix D: Consequences for Individuals) outlines the consequences of non compliance of the Directive. Consequences can include discipline or other forms of administrative actions that reflect a graduated, progressive scale to allow for the tailoring of an action appropriate to the given situation. Where criminal activity is suspected, the Government Security Policy is to be followed.

8. The UK also provides guidance to its public authorities on automation in public administration called the Technology Code of Practice (TCoP). The TCoP contains criteria to help public service officers design, build and buy technology.

III. Supervisory authority and other related oversight bodies

9. Part 2 of Ireland’s Data Protection Act 2018 concerns the creation and powers of its Data Protection Commission. It is a statutory body with broad power to carry out is supervisory function such as:

- Section 12(5) – The Commission shall have all such powers as are necessary or expedient for the performance of its functions.

- Section 12(6) – The Commission shall disseminate, to such extent and in such manner as it considers appropriate, information in relation to the functions performed by it.

- Section 12(7) – The Commission shall be independent in the performance of its functions.

- Section 12(8) – Subject to this Act, the Commission shall regulate its own procedures.

- Article 16 – Appointment of a Commissioner(s) for Data Protection via a an open selection competition held by the Public Appointments Service

- Article 19 – Commissioner accountability to an appointed parliamentary committee.

- Article 24 – Submit an annual report not later than 30 June in each year and publish it in such a form and manner as it considers appropriate.

10. In 2019, Denmark created a Data Ethics Council that aims to create a forum that can partly create a data ethics debate, and partly continuously support a responsible and sustainable use of data in business and the public sector. The Council is an independent, public administration authority that takes a soft law approach by recommending best practices as oppose to the traditional coercive measures of legislative penalties. The Council has developed tools on the considerations public authorities should make before deciding on the use of data in new technologies: data ethics assessment form and data ethics impact assessment.

IV. Attracting and retaining relevant expertise in the public service

11. The knowledge asymmetry between public servants seeking to automate public administration and the eventual supplier of the ADS is great. Recognising this problem Singapore provides a competitive salaries and favourable working conditions in the public service to attract and retain world-class professionals. The country’s Government Technology Agency (GovTech), which is part of the Smart Nation and Digital Government Group within the Prime Minister’s Office, operates as a company, harnessing digital technology to develop and deliver digital products and services to people, businesses and the Government as part of the public sector digital transformation process.13 It recovers innovation costs by including them in product pricing, which is approved by the Ministry of Finance.14

V. Measures for protecting vulnerable groups

12. Many jurisdictions reviewed implemented practical solutions for protecting vulnerable groups in their drive towards digital transformation, that could not be solved in the design of the ADS. For example moving manual forms to online forms may be difficult for older persons who are not computer literate. Singapore’ssolution to this issue is its creation of digital community hubs where one-on-one guided learning sessions are offered to help older persons navigate digital government. Singapore has created a suite of activities to help older persons via its Seniors Go Digital. Not everyone can afford a computer or a smart phone and if automation of welfare applications can only be made online an alternative must be found. In Australia the public welfare office, Centrelink (“local service centre”), offers computer kiosks and staff are available to guide individuals through the online application process.

D. What we missed

- Ex ante measures

1. In general opportunities were missed in the regulation reviewed to strengthen ex ante regulatory measures around whether or not to automate legislative acts of public administration. Furthermore, clear requirements for the subsequent design, testing and continuous monitoring of the ADS was missing. As Lord Sales, Justice of the UK Supreme Court noted in his Sir Henry Brooke Lecture “Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence and the Law”:

“Often there is no one to blame. [Quoting from James Williams books Stand Out of Our Light] “At ‘fault’ are more often the emergent dynamics of complex multiagent systems rather than the internal decision-making dynamics of a single individual”.

Given the legal consequences and human rights implications of legislative acts of public administration any decision to automate should proceed with caution. In the example of Robodebt there existed a process for the Data Commission to review the use of data in public administration automation but the Data Commission was not consulted in the development of the Robodebt scheme. Hence, we recommend that regulations be developed to guide the decision-making process of whether or not to automate acts of public administration, and include penalties for non compliance.

- Relaxing rules and extenuating circumstances

2. If government sets a plan for digital government, public service officers are required to develop ideas and projects that operationalise the plan. In a situation where a legislative act of public administration is to be automated, an ADS not capable of considering extenuating circumstances or relaxing a rule to meet the ‘equity’ of a case may be deployed because the desire to achieve the plan of government trumps other goals.15 It may be true that in hundreds of thousands of decisions of public administration only one situation merits “relaxing a rule” but the consequences of the ADS not making that consideration may have dire consequences for that individual. There are many examples of automated public administration that show that to be true: UK, Australia, US, Netherlands.

- Impact assessments

3. Ex ante regulatory measures could require an impact assessment and make clear the matters to be included:

- outline the legislative basis of the act of public administration and make clear the rules to be followed, particularly the considerations, balancing and other tests used where discretion is permitted by legislation;

- case studies examining the human rights impact for groups of vulnerable people;

- the process by which the technology designed integrates or internalises these rules;

- the testing protocol to be used to ensure confidence and consistency of the ADS;

- management system for continuous monitoring; and

- where conflict of policy goals may occur how they are to be resolved.

4. The impact assessment should be approved by a diverse range of experts who are independent, possibly sitting under parliamentary scrutiny. Where an ADS uses algorithms this may require the creation of an ‘Algorithm Commission‘. Lord Sales in the same lecture proposed the creation of such a Commission led by an independent group of experts tasked with reviewing proposed algorithms, at ‘the ex ante design stage,’:

“The creation of an algorithm commission would be part of a strategy for meeting … – (i) lack of technical knowledge in society and (ii) preservation of commercial secrecy in relation to code. The commission would have the technical expertise and all the knowledge necessary to be able to interrogate specific coding designed for specific functions. I suggest it could provide a vital social resource to restore agency for public institutions – to government, Parliament, the courts and civil society – by supplying the expert understanding which is required for effective law-making, guidance and control in relation to digital systems. It would also be a way of addressing … – (iii) rigidity in the interface between law and code – because the commission would include experts who understand the fallibility and malleability of code and can constantly remind government, Parliament and the courts about this.”16

Many jurisdictions reviewed did have an independent “Data Protection Commission”, particularly EU Member States as a requirement of the GDPR, however, its mandate and expertise is insufficient to also cover algorithms.

- Supervisory commission

5. The US state of Massachusetts is considering Bill H.2701, an Act Establishing a Commission on Automated Decision-making, artificial intelligence, transparency, fairness and individual rights. The proposed Massachusetts Commission will study and make recommendations about the state’s use of ADS that may affect human welfare, including but not limited to legal rights and privileges of individuals. The Massachusetts Commission shall examine the following on an ongoing basis, which are commendable:

(i) a complete and specific survey of all uses of automated decision systems by the commonwealth of Massachusetts and the purposes for which such systems are used;

(ii) the principles, policies, and guidelines adopted by specific Massachusetts offices to inform the procurement, evaluation, and use of automated decision systems, the procedures by which such principles, policies, and guidelines are adopted, and any gaps in such principles, policies, and guidelines;

(iii) the training specific Massachusetts offices provide to individuals using automated decision systems, the procedures for enforcing the principles, policies, and guidelines regarding their use, and any gaps in training or enforcement;

(iv) the manner by which Massachusetts offices validate and test the automated decision systems they use, and the manner by which they evaluate those systems on an ongoing basis, specifying the training data, input data, systems analysis, studies, vendor or community engagement, third-parties, or other methods used in such validation, testing, and evaluation;

(v) matters related to the transparency, explicability, auditability, and accountability of automated decision systems, including information about their structure; the processes guiding their procurement, implementation and review; whether they can be audited externally and independently; and the people who operate such systems and the training they receive;

(vi) the manner and extent to which Massachusetts offices make the automated decision systems they use available to external review, and any existing policies, laws, procedures, or guidelines that may limit external access to data or technical information that is necessary for audits, evaluation, or validation of such systems;

(vii) the due process rights of individuals directly affected by automated decision systems, and the public disclosure and transparency procedures necessary to ensure such individuals are aware of the use of the systems and understand their related due process rights;

(viii) uses of automated decision systems that directly or indirectly result in disparate outcomes for individuals or communities based on age, race, creed, colour, religion, national origin, gender, disability, sexual orientation, marital status, veteran status, receipt of public assistance, economic status, location of residence, or citizenship status;

(ix) technical, legal, or policy controls to improve the just and equitable use of automated decision systems and mitigate any disparate impacts deriving from their use, including best practices and policies developed through research and academia or in other states and jurisdictions;

(x) matters related to data sources, data sharing agreements, data security provisions, compliance with data protection laws and regulations, and all other issues related to how data is protected, used, and shared by agencies using automated decision systems;

(xi) matters related to automated decision systems and intellectual property, such as the existence of non-disclosure agreements, trade secrets claims, and other proprietary interests, and the impacts of intellectual property considerations on transparency, explicability, auditability, accountability, and due process; and

(xii) any other opportunities and risks associated with the use of automated decision systems by Massachusetts offices.

- Ex post measures

6. Evidently, it would be more optimal that a good ex ante regulatory framework prevented ill-designed ADS, nevertheless the minimum ex post measures should include requirements to inform individuals that they are the subject of an ADS, providing clear reasons for the decision and outlining the process for challenging the decision. EU Member States implementing the GDPR generally had some form of these measures. However, opportunities for greater transparency and minimum requirements for ongoing monitoring and continuous improvement (although the Canadian Directive did have the latter) were missing.

- Alert mechanisms

7. In addition to ensuring measures for administrative review are simple and easily accessible, whistle-blowing protections aimed at public servants or contractors could be strengthened as another form of accountability. We wrote about how to strengthen whistle-blowing regulations in our article “Whistleblowers: protection, incentives and reporting channels as a safeguard to the public interest”.

- Auditing

8. Basic audit function is a common feature of most public administrations. Whether it be the internal departmental audit directorate responsible for auditing programmes and decisions of the public authority or an external, independent public authority that audits all public authorities. Given the trend towards automation of public administration the mandates of either internal or external audit authorities could specifically include annual audits of ADS, to require examination of:

- number of complaints received about the ADS, including statistics about the resolution of the complaints;

- effectiveness of ongoing monitoring and testing of the ADS;

- the qualifications and expertise of public servants and contractors involved in the ADS programme; and

- estimated savings and costs of the ADS.

E. Useful reference material about the automation of public administration

Very good site for thinking about the design of ADS in government: https://automating.nyc/

New Zealand government agencies have signed up to an Algorithm Charter committing to carefully manage how algorithms are used in their agencies. New Zealand also completed a review of how government uses algorithms via a self-assessment tool, the results of which are informative for other jurisdictions.

Australia has a legislative development process underway for new legislation to reform public sector data use, which aims to streamline and modernise how the Australian government shares data, while ensuring privacy and security.

Report on algorithm decision-making in Latin America: https://www.derechosdigitales.org/wp-content/uploads/glimpse-2019-4-eng.pdf

E-government in Africa: https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/gdi/publications/workingpapers/igov/igov_wp13.pdf

Council of Europe report on algorithms and human rights: https://rm.coe.int/algorithms-and-human-rights-en-rev/16807956b5

Expert systems in government: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232617542.pdf

Veale, M. & Brass, I., “Administration by Algorithm? Public Management meets Public Sector Machine Learning”, Algorithm Regulation, ed. Yeung, K. & Lodge, M., 2019,https://michae.lv/static/papers/2019administrationbyalgorithm.pdf.

Hong, C.M., “Towards a Digital Government Reflections on Automated Decision-Making and the Principles of Administrative Justice”, (2019) 31 SacLJ 875 (published on e-First 26 Sept 2019),https://www.academypublishing.org.sg/Journals/Singapore-Academy-of-Law-Journal/e-Archive/ctl/eFirstSALPDFJournalView/mid/495/ArticleId/1453/Citation/JournalsOnlinePDF.

Algorithm Watch is a non-profit research and advocacy organisation that evaluates algorithmic decision-making processes and designs best practices. It has evaluated the ADS of many EU states:https://algorithmwatch.org/en/automating-society-recommendations/

Analysis and Policy Observatory Review into bias in algorithmic decision-making https://apo.org.au/node/309799

Automation in tax administration: https://globtaxgov.weblog.leidenuniv.nl/2019/10/22/no-taxation-without-automation/

Automation in tax administration combined with the project management approach: The Data Intelligent Tax Administration – PwC (We usually avoid links to companies. However, in this case, the explanatory value of this document was particularly useful. It is not that we recommend PwC or any other consultancy.)

This article was written by Valerie Thomas, on behalf of the Regulatory Institute, Brussels and Lisbon.

1 Kohler, M., The Handbook: How to regulate? 2014, p. 20, https://www.howtoregulate.org/the-handbook/.

2 Report of Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Phillip Alston, Extreme poverty and human rights submitted to 74th Session of UNGA Agenda item 70(b), 11 Oct 2019, p. 2, https://undocs.org/A/74/493.

3 Guidance issued by the Administrative Review Council in 2004 warned that ‘expert systems should not automate the exercise of discretion’ (Principle 2) Administrative Review Council Automated Assistance in Administrative Decision Making, Report to the Attorney-General (Report No. 46) (November 2004), p. viii, https://www.ag.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-03/report-46.pdf.

12 OECD Comparative Study, “Digital Government Strategies for Transforming Public Services in the Welfare Areas”, pp. 53-54, http://www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/Digital-Government-Strategies-Welfare-Service.pdf.

16 Lord Sales Lecture on “Algorithms, Artificial Intelligence and the Law”, 12 Nov 2019, p. 13, https://www.supremecourt.uk/docs/speech-191112.pdf.