Regulating the police, particularly use of force and oversight of police power, received global attention following the death in Minneapolis police custody of George Floyd on 25 May 2020. The police is one of a few state institutions (others include the military, prisons) that are authorised to use force. According to German sociologist Max Weber the successful monopoly over legitimate physical force is what defines a modern state. Recognising that the police provide important services such as law enforcement and public safety, this howtoregulate article focusses on how best to regulate the police noting the range of functions they must perform in service of the public interest.

A. International and supra-national regulatory framework

I. United Nations

1. International human rights treaties are binding on States Parties that adopt them, including their agents, such as the police. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, all touch on aspects of regulating police power, as well as a number of treaties dealing with specific topics, such as:

- International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD);

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and its Optional Protocol;

- Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) and its Optional Protocol (OPCAT); and

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and its Optional Protocols on the involvement of children in armed conflict and on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography.

2. These various treaties have also been complemented by soft law documents that provide detailed guidance and establish detailed human rights standards. The following soft law documents, are of particular relevance to the regulation of police:

- Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials (CLEO);

- Basic Principles for the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials (BPUFF);

- Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (SMR);

- Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment;

- Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power (Victims Declaration).

3. The key measures in the CLEO for regulating the police, consistent with the above Conventions, include:

- Article 1: Law enforcement officials shall at all times fulfil the duty imposed upon them by law, by serving the community and by protecting all persons against illegal acts, consistent with the high degree of responsibility required by their profession.

- Article 2: In the performance of their duty, law enforcement officials shall respect and protect human dignity and maintain and uphold the human rights of all persons.

- Article 3: Law enforcement officials may use force only when strictly necessary and to the extent required for the performance of their duty.

- Article 5: No law enforcement official may inflict, instigate or tolerate any act of torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, nor may any law enforcement official invoke superior orders or exceptional circumstances such as a state of war or a threat of war, a threat to national security, internal political instability or any other public emergency as a justification of torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

- Article 6: Law enforcement officials shall ensure the full protection of the health of persons in their custody and, in particular, shall take immediate action to secure medical attention whenever required.

- Article 7: Law enforcement officials shall not commit any act of corruption. They shall also rigorously oppose and combat all such acts.

4. The key principles for the police use of force outlined BPUFF, consistent with the above Conventions, include:

General Provisions

(2) Governments and law enforcement agencies should develop a range of means as broad as possible and equip law enforcement officials with various types of weapons and ammunition that would allow for a differentiated use of force and firearms. These should include the development of non-lethal incapacitating weapons for use in appropriate situations […]

(3) The development and deployment of non-lethal incapacitating weapons should be carefully evaluated in order to minimise the risk of endangering uninvolved persons, and the use of such weapons should be carefully controlled.

(4) Law enforcement officials, in carrying out their duty, shall, as far as possible, apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms. They may use force and firearms only if other means remain ineffective or without any promise of achieving the intended result.

(5) Whenever the lawful use of force and firearms is unavoidable, law enforcement officials shall:

a) Exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence and the legitimate object to be achieved;

b) Minimise damage and injury, and respect and preserve human life; and

c) Ensure that assistance and medical aid are rendered to any injured or affected persons at the earliest possible moment.

(7) Governments shall ensure that arbitrary or abusive use of force and firearms by law enforcement officials is punished as a criminal offence under their law.

(8) Exceptional circumstances such as internal political instability or any other public emergency may not be invoked to justify any departure from these basic principles.

Special Provisions

(9) Law enforcement officials shall not use firearms against persons except in self-defence or defence of others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury, to prevent the perpetration of a particularly serious crime involving grave threat to life, to arrest a person presenting such a danger and resisting their authority, or to prevent his or her escape, and only when less extreme means are insufficient to achieve these objectives. In any event, intentional lethal use of firearms may only be made when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.

Policing unlawful assemblies

(12) As everyone is allowed to participate in lawful and peaceful assemblies, in accordance with the principles embodied in the UDHR and the ICCPR, governments and law enforcement agencies and officials shall recognise that force and firearms may be used only in accordance with principles 13 and 14.

(13) In the dispersal of assemblies that are unlawful but non-violent, law enforcement shall avoid the use of force or, where that is not practicable, shall restrict such force to the minimum extent necessary.

(14) In the dispersal of violent assemblies, law enforcement officials may use firearms only when less dangerous means are not practicable and only to the minimum extent necessary […]

Policing persons in custody or detention

(15) Law enforcement officials, in their relations with persons in custody or detention, shall not use force, except when strictly necessary for the maintenance of security and order within the institutions, or when personal safety is threatened.

(16) Law enforcement officials, in their relations with persons in custody or detention, shall not use firearms, except in self-defence or in the defence of others against the immediate threat of death or serious injury, or when strictly necessary to prevent the escape of a person in custody or detention […]

5. The UN regulates the national police forces that contribute to provide policing services to peacekeeping missions (UNPOL) around the world. All UN personnel, including UNPOL are required to comply with the UN Charter and the Policy on Accountability for Conduct and Discipline in Field Missions, and the police have additional specific regulations, including:

- Guidelines for UNPOL on Assignment with Peacekeeping Operations;

- Revised draft model Memorandum of Understanding between the UN and Police/Troop Contributing Countries, incorporating the annex “We are the UN Peacekeeping Personnel”;

- Secretary-General’s Bulletin on Regulations Governing the Status, Basic Rights and Duties of Officials other than Secretariat Officials, and Experts on Mission;

- Secretary-General’s Bulletin on Observance by United Nations forces of international humanitarian law;

- Directives for Disciplinary Matters involving Civilian Police Officers and Military Observers;

- Ten Rules/Code of Personal Conduct for Blue Helmets; and

- Other Administrative Issuances, including use of information and communication technology.

The UN’s Standing Police Capacity (SPC) provide rapid, deployable police expertise to UN operations, post conflict and other crisis situations. The SPC are also regulated by the same rules as UNPOL.

7. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime have developed a Handbook on Police Accountability, Oversight and Integrity, which concerns best practices for accountability, which is defined as a system of internal and external checks and balances aimed at ensuring that police carry out their duties properly and are held responsible if they fail to do so.

II. International Criminal Police Organisation (INTERPOL)

8. INTERPOL was created in 1956 following the adoption of its Constitution at the 25th General Assembly in Vienna by its members. INTERPOL helps the police forces in its members’ countries to make the world a safer place by enabling them to share and access data on crimes and criminals, and by offering a range of technical and operational support. INTERPOL agents have no powers to arrest but liaise with national police services to carry out any arrests. INTERPOL has two categories of international staff, seconded officials from Member States’ police service on a fixed term contract and directly recruited officials on a fixed-term contract or indeterminable period. All international staff are recruited on the basis of efficiency, competency and integrity, and each recruitment notice outlines the education and experience required for each role. Focussing only on seconded officials from national police services, the senior grade officials (1 and 2) are required to have a minimum of 5 years higher university degree and law enforcement training at a senior to command level. Middle-ranking officials (Grade 5) are required to have either a 3-4 years education at an accredited university or other specialised higher education establishment in a relevant field as well as a minimum 3 years experience as a law enforcement officer or a minimum of 10 years experience as a law enforcement officer.

9. The INTERPOL Staff Manual covers the duties, obligations, administration, recruitment, conditions of service, disciplinary, resolution of disputes and salary scales of INTERPOL staff.

Regulation 12.1 of the Manual provides that disciplinary measures or summary dismissal may be imposed on staff for:

Rule 12.1.1: Unsatisfactory conduct and misconduct

(1) Any act or omission, whether deliberate or resulting from negligence committed by an official in contravention of the terms of his declaration of loyalty, of the Staff Regulations, Staff Rules or Staff Instructions, or of the standards of conduct befitting his status as an international official, may constitute unsatisfactory conduct within the meaning of Regulation 12.1 and may lead to the institution of disciplinary proceedings and the imposition of disciplinary measures for unsatisfactory conduct or misconduct.

(2) Misconduct is understood as a particularly serious unsatisfactory conduct which may warrant the official’s dismissal or summary dismissal in accordance with rule 12.1.3(1) (i) and (j).

The Manual at Rule 12.1.3 lists 10 disciplinary measures that may be imposed from a reprimand, fine or downgrading, through to a summary dismissal with forfeiture of allowances. Imposing a disciplinary measure must be proportionate to seriousness of the unsatisfactory conduct. Rule 12.1.4 (2) provides that in assessing seriousness of the unsatisfactory conduct 8 criteria shall be taken into consideration such as:

-

- the degree to which the standard of conduct was breached;

- the gravity of the damage caused to INTERPOL;

- the recurrence of unsatisfactory conduct;

- the position of the staff member;

- collusion with other staff members

- whether the unsatisfactory conduct was a deliberate act or committed through gross negligence;

- length of service;

- admission of the unsatisfactory conduct prior to the date the unsatisfactory conduct is discovered and any action taken by the official to mitigate any adverse consequences resulting from his unsatisfactory conduct

Rule 12.1.4 (3) states that dismissal is appropriate where misconduct is serious or recurrent; in cases where threats are made; misuse of public funds; deliberate false statements, misrepresentation or fraud; and when the breach of trust is so serious that continuation of the official’s services is not in INTERPOL’s interest.

III. Europe

(a) European Police Office (Europol)

10. As a unique model of regional policing, we present the European Union’s (EU) law enforcement agency (currently administered under Regulation (EU) 2016/794, hereinafter Europol Regulation), whose main goal is to achieve a safer Europe for the benefit of all EU citizens. Europol supports the 27 EU Member States in their fight against terrorism, cybercrime and other serious and organised forms of crime. Europol provides services that support law enforcement operations on the ground, act as a hub for information on criminal activities and are a centre of law enforcement expertise. Its mandate includes activities in the following areas: 11. Europol employs around 100 criminal analysts, which is one of the largest concentrations of analytical capability in the EU and uses state-of-the-art tools to support national law enforcement agencies’ investigations1. Europol is headed by a Director, that is experienced in law enforcement and is appointed by the EU Council. Europol is an agency of the EU, and in each Member State Europol has legal capacity accorded to legal person under national law, in particular, acquire and dispose of movable and immovable property and be a party to legal proceedings (Europol Regulation Chapter XI, Article 62). The privileges and immunities of Europol and its staff is outlined in Protocol No 7 of the Treaty of the EU (TEU) and the Treaty of the Functioning of the EU (TFEU). Chapter 5, Article 88(3) of TEU provides that “Any operational action by Europol must be carried out in liaison and in agreement with the authorities of the Member State or States whose territory is concerned. The application of coercive measures shall be the exclusive responsibility of the competent national authorities”. Europol do not carry firearms even when staff are deployed to operations.

11. Europol employs around 100 criminal analysts, which is one of the largest concentrations of analytical capability in the EU and uses state-of-the-art tools to support national law enforcement agencies’ investigations1. Europol is headed by a Director, that is experienced in law enforcement and is appointed by the EU Council. Europol is an agency of the EU, and in each Member State Europol has legal capacity accorded to legal person under national law, in particular, acquire and dispose of movable and immovable property and be a party to legal proceedings (Europol Regulation Chapter XI, Article 62). The privileges and immunities of Europol and its staff is outlined in Protocol No 7 of the Treaty of the EU (TEU) and the Treaty of the Functioning of the EU (TFEU). Chapter 5, Article 88(3) of TEU provides that “Any operational action by Europol must be carried out in liaison and in agreement with the authorities of the Member State or States whose territory is concerned. The application of coercive measures shall be the exclusive responsibility of the competent national authorities”. Europol do not carry firearms even when staff are deployed to operations.

12. Chapter III of the Europol Regulation concerns the organisation of Europol and contains detailed provisions about the management, its structure (requiring gender balance on the Management Board) and multiannual work programme. Chapter V, Section 2 contain strict provisions around transfer and exchange of personal data. Chapter VI concerns detailed data protection safeguards around processing, time limits for storage and erasure, security of processing and requires Europol to implement data protection by design in its technical and organisational procedures. Europol’s activities are scrutinised (Chapter VIII) by the European Parliament together with national parliaments, comprising a Joint Parliamentary Scrutiny Group (JPSG). The JPSG “shall politically monitor Europol’s activities in fulfilling its mission, including as regards the impact of those activities on the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons” [Article 51(2)] and may request other relevant documents necessary to fulfil its monitoring function [Article 51(4)].

13. Similar to INTERPOL, Europol also has direct recruitment for staff and seconded national experts from national law enforcement agencies. Financial oversight of Europol is governed in the same way as other EU agencies via the European Court of Auditors, Internal Audit Service and the Internal Audit Capability. The European Ombudsman also has powers to receive complaints from the public concerning maladministration of Europol.

(b) Organisation for Security Cooperation Europe (OSCE)

14. The OSCE developed a Guidebook on Democratic Policing for OSCE staff to manage police and law enforcement issues, assist police practitioners and policy makers to develop and strengthen democratic policing and to serve as a reference for international adopted standards. The Guidebook articulates the objectives of democratic police services and forces; the importance of their commitment to the rule of law, policing ethics, and human rights standards; the essential nature of police accountability to the law and to the society they serve; as well as the need for their co-operation with the communities, recognising that effective policing requires partnership with the communities being served.

(c) Council of Europe (CoE)

15. Recommendation (2001)10 on the European Code of Police Ethics (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 19 September 2001 at the 765th meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies) applies to police services, or to other publicly authorised and/or controlled bodies with the primary objectives of maintaining law and order in civil society, and who are empowered by the state to use force and/or special powers for these purposes. The aim of the Code is to guide Member States on the regulation of their police services in line with democratic policing principles. The CoE also published a Toolkit on legislating for the security sectors.

B. National regulations

I. Policing model

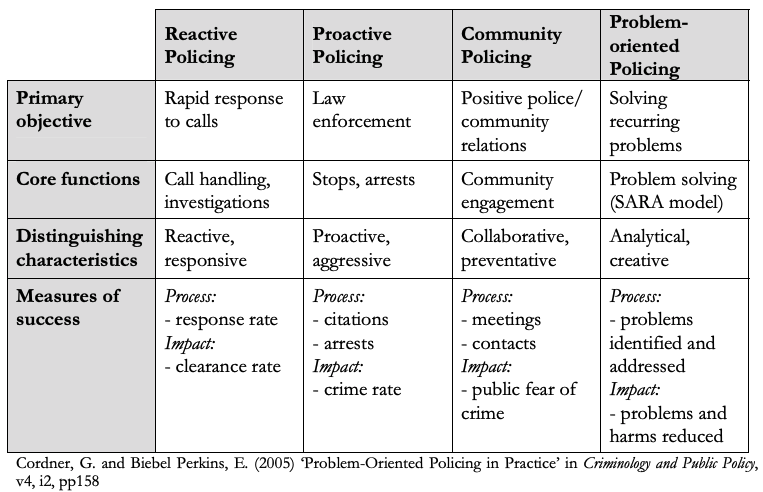

1. There exist many different types of policing models2 around the world, which have evolved in a mostly reactive manner. For example one of the earliest professional police forces in the world was established in London by the Metropolitan Police Act 1829, because the former parish system was inadequate for a rapidly industrialising city. Many jurisdictions have several layers of policing covering federal, state, municipal and sometimes parish level, which often requires a complex regulatory scheme. Research of many jurisdictions’ police regulation for this howtoregulate article shows that centralised police models do better than de-centralised police models because economies of scale can be achieved in resource intensive areas such as police training, oversight and standards enforcement. Other jurisdictions have completed major police reforms using a consultative approach with the public and parliament, such as New Zealand and in some US cities, political pressure responding to public complaints of excessive police force have spawned reforms via federal consent decrees with local police departments. The following table below shows the various policing models that exist.3

2. In reviewing several jurisdiction’s approach to regulating police, New Zealand’s approach to reforming and consolidating its multiple police legislation represents a best practice approach. Conveniently, the reform process followed by the New Zealand government is outlined in one website, the Police Act Review. New Zealand uses a community policing model which is recognised in several parts of the Policing Act 2008:

2. In reviewing several jurisdiction’s approach to regulating police, New Zealand’s approach to reforming and consolidating its multiple police legislation represents a best practice approach. Conveniently, the reform process followed by the New Zealand government is outlined in one website, the Police Act Review. New Zealand uses a community policing model which is recognised in several parts of the Policing Act 2008:

- Section 8(c) This Act is based on the following principles – “policing services are provided under a national framework but also have a local community focus”;

- Section 9(e) The functions of the police include – “community support and reassurance”; and

- Section 10(2) “It is also acknowledged that it is often appropriate, or necessary, for the Police to perform some of its functions in co-operation with individual citizens, or agencies or bodies other than the Police”.

3. Kenya is an example of a jurisdiction that created a new police structure under the National Police Service Act 2011 by bringing together two separate police forces into one national police service. Like New Zealand they also adopted a community policing model, Section 2. Interpretation (1):

“community policing” means the approach to policing that recognises voluntary participation of the local community in the maintenance of peace and which recognises that the police need to be responsive to the communities and their needs, its key element being joint problem identification and problem solving, while respecting the different responsibilities the police and the public have in the field of crime prevention and maintaining order.

Kenya’s Police Act is interesting in that command is with the Inspector General, although the relevant Cabinet Secretary may give a direction in writing about any matter of policy of the police service [Section 8A (5)]. The Inspector General is responsible for command and discipline (Section 8), functions and powers of the Inspector General are proscribed under Section 10 with many details concerning audit function, budget and financial management. Qualifications for appointments as Inspector General are outlined at Section 11, including educational requirements (university degree), distinguished career and must have served a minimum of 15 years in a variety of disciplines [listed at Section 11 (1) (e) eg. criminal justice, strategic management, sociology]. Section 5 requires gender, ethnic and regional balance in the police, “(a) uphold the principle that not more than two-thirds of the appointments shall be of the same gender; and (b) reflect the regional and ethnic diversity of the people of Kenya.”. More information about Kenya police reform can be found here.

II. Police Recruitment

4. Korea has three recruitment pathways into the Korean National Police Agency (KNPA):

- National exam police officer: Following acceptance based on test scores [extremely rigorous physical, knowledge and interview testing (in Korean)], recruits undergo 34 week training (1190 hours), which includes a strict schedule of training on the law, field training and police responses. Recruits must 90% of the training and achieve more a minimum of 60% in test scores before graduating as an officer and are subject to two years of on-the-job training with higher ranked officers in different departments and police stations.4

- National Police university.

- Military service police: Males (18-30 years of age) completing compulsory 18 month military service may do so in the KNPA. Recruits must pass a physical test and personality test, then complete 5 weeks of military training, then 3 weeks of police training. They are a lower rank than an officer and are grouped in separate categories, and are limited to tasks involving traffic control, public protest management and crime prevention/presence patrols.

5. In the Australian state of Victoria, to apply as a Victoria Police recruit you must:

- be over 18 (if under 21 years of age you must include your high school certificate),

- of good character and reputation (prior offences may be a cause for disqualification),

- be an Australian citizen (or New Zealand citizen with a special category visa),

- pass a fitness test, Australian driver’s licence,

- hold a First Aid Certificate,

- pass minimum medical requirements,

- be able to communicate effective (tested). It is critical that police are able to give and receive verbal information in stressful situations. If an applicant is identified during the process as having a possible issue in this area, they are given the opportunity to participate in a process to assess their level of verbal communication skills in the context of operational suitability and safety,

- declare associations to determine any conflicts of interest, and

- show a work history evidencing drive, willingness to work and initiative (work history assessment is a good predictor of ultimate success, the recruitment process includes a video screening interview, 1:1 psych interview and panel requiring applicants to relate lived experiences to answer the behavioural questions that are posed).5

The above process takes between 6-9 months to complete, depending on how long an applicants history must be checked. The recruits then complete 12 weeks of training at the Victoria Police Academy and on graduating recruits become a probationary constable for two years in which ongoing training is required.6

III. Police Empowerments

6. Police empowerments are usually directly provided in legislation, or proscribed in rules or policies pursuant to powers delegated by legislation. The latter being the most common method used in the 18,000 federal, state, county, and local agencies of law enforcement in the US and small town police departments of 10 or fewer officers make up the majority.7 Empowerments should be unambiguously proscribed in the regulation, particularly around use of force and deprivation of liberty, and best practice indicates that regulation should articulate what is forbidden.

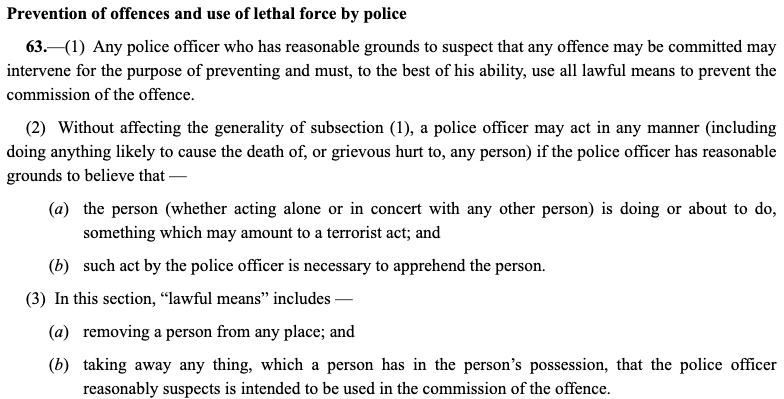

7. In Singapore most of the police empowerments are contained in the Criminal Procedure Code (Chapter 68) and examples of some empowerments include (not exhaustive):

- Part IV Information to police and powers of investigation covers duties on receiving information about offences, search and seizure and powers of investigation for offences related to statement recording.

- Part V Prevention of offences covers security for keeping peace and for good behaviour and unlawful assemblies.

- Part VI Arrest and bail an processes to compel appearance covers powers of arrest without warrant and arrest with warrant.

Singapore’s regulation around use of force is unambiguously outlined in the Code at Part V, Division 4, Section 63: 8. Singapore’s Police Force Act outlines the empowerments of its police in Division 1 – Duties of police officers, notable empowerments (not exhaustive) include:

8. Singapore’s Police Force Act outlines the empowerments of its police in Division 1 – Duties of police officers, notable empowerments (not exhaustive) include:

- being armed (Section 22);

- “for the maintenance and preservation of law and order or for the prevention or detection of crime … (a) erect or place barriers in or across any public road or street or in any public place in such manner as he may think fit … (b) take all reasonable steps to prevent any vehicle being driven or ridden past any such barrier” (Section 26)

- special powers for dealing with attempts to suicide, including preventing personal injury, hurt or death to any persons, preserving evidence, seize property, conduct searches without a search warrant and demand entry (or force entry by breaking) where an officer suspects that a person is about to or has attempted to commit suicide (Sections 26A, 26B, 26C and 26D).

9. In the US state of New York the regulation covering police empowerments are outlined in the Patrol Guide (PG). PG 221-01 concerns the “Force Guidelines” for use of force which specifically prohibits:

- Discharge a firearm when, in the professional judgment of a reasonable member of the service, doing so will unnecessarily endanger innocent persons;

- Discharge firearms in defence of property;

- Discharge firearms to subdue a fleeing felon who presents no threat of imminent death or serious physical injury to the member of service or another person present;

- Fire warning shots;

- Discharge firearm to summon assistance, except in emergency situations when someone’s personal safety is endangered and no other reasonable means to obtain assistance is available;

- Discharge their firearms at or from a moving vehicle unless deadly physical force is being used against the member of the service or another person present, by means other than a moving vehicle;

- Discharge firearm at a dog or other animal, except to protect a member of the service or another person present from imminent physical injury and there is no opportunity to retreat or other reasonable means to eliminate the threat;

- Cock a firearm. Firearms must be fired double action at all times;

- There is a note that “Drawing a firearm prematurely or unnecessarily limits a uniformed member’s options in controlling a situation and may result in an unwarranted or accidental discharge of the firearm. The decision to display or draw a firearm should be based on an articulable belief that the potential for serious physical injury is present. When a uniformed member of the service determines that the potential for serious physical injury is no longer present, the uniformed member of the service will holster the firearm as soon as practicable”.

The Force Guidelines require members of the service to use de-escalation techniques and to consider whether a subject’s lack of compliance might be related to a medical condition, mental impairment, development disability, physical limitation, language barrier and/ or drug interaction. Where a mental impairment may be involved the member of service must comply with the PG 221.13 “Mentally Ill or Emotionally Disturbed Persons”.

10. Other regulations on topics concerning types of use of force or other empowerments:

- New York’s Guidelines for pepper spray devices.

- Iceland’s Police Act 1996 obliges the police “to take charge of children under the age of 16 who are found in places where their health or welfare are in serious danger” (Article 18).

- New Zealand uses a Schedule in its Policing Act 2008 to list the empowerments of particular duties and the seniority such duties require, interestingly New Zealand police are not armed, it recently conducted a trial to determine whether specialist units should carry arms and decided against doing so.

IV. Police training

11. Australia has eight police services, one of which is the federal police generally focussed on federal crimes (human trafficking, terrorism, intellectual property crime, cyber crime etc.). Although Australia has eight different police services, they have all worked together to ensure common training standards thereby reducing inefficiencies and facilitating movement of police members to different police services. The Police Training Package is a joint training initiative of the Australian and state and territory governments about the skills that Australian police officers should have regardless of where they police. This module covers use of force and how the competency is structured.

12. Chapter VIII of Iceland’s Police Act 1996 concerns the training of the police and the Centre for Police Training and Professional Development has contracted responsibility for education in general police matters to trainee police to a university institution. The university contracted is responsible for delivering the two-year Police Science diploma. The Icelandic Centre also supervises the continuous training and education for existing police members.

V. Monitoring, oversight and transparency

13. Best practice regulation for any monitoring and oversight function of public services, particularly the police given their broad ranging powers to use force and detain, should be independent and include the public.

14. Sierra Leone operates a simple monitoring and oversight framework of its police through the Independent Police Complaints Board Regulations 2013 established the Independent Police Complaints Board with the following functions at Section 3:

- investigate deaths in police custody;

- fatal road accidents involving police vehicles;

- shooting incidents where the police discharged a firearm or killed a personality;

- incidents where police caused injury, assault or wounds;

- allegations of misconduct;

- any matter or incident the Board thinks the action or inaction of the police is likely to impact significantly on the confidence of the people in the police, which enables the Board to track complaints over time to establish any trends or pattern of abuse by police including in specific regions or districts8; and

- provide advice on ways such incidents involving police may be avoided or eliminated.

The Board has the same powers, rights and privileges as the High Court of Justice at a trial to compel witnesses and examine them under oath and compelling the production of documents as well as the power to require a person to provide information or to answer any question in connection to an investigation by the Board (Section 6). The Board may conduct an investigation on its own initiative or on the basis of a complaint (which may be anonymous), which has a time limit of not later than one year following the matter alleged in the complaint (Sections 9 and 10). The Chairman of the Board is appointed by the President of Sierra Leone from persons with formal qualifications in any profession or discipline relevant to the functions of the Board and the remaining six members of the Board are proscribed at Section 1, including:

- a Commissioner of the Human Rights Commission of Sierra Leone selected by members of the Commission;

- a representative of the Sierra Leone Bar Association;

- a representative of the Anti-Corruption Commission;

- a representative of the Inter-Religious Council;

- a representative of the Police Council who is not a member of the police; and

- a retired senior police officer selected by the Minister responsible for Internal Affairs on the advice of the Inspector-General of Police.

15. New Zealand’s Independent Police Conduct Authority is statutorily independent under the Independent Police Conduct Authority Act 1988 and represents a high watermark for an independent authority. The Parliament recommends to the Governor General who should make up the five member Authority, including the appointment of Chairperson, who must be a serving or retired judge (Sections 5 and 5A). The Authority is required to act independently under Section 4AB. The Authority has broad ranging powers to receive complaints and “to investigate of its own motion, where it is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to carry out an investigation in the public interest, any incident involving death or serious bodily harm notified to the Authority by the [Police] Commissioner” (Section 12). The power to receive complaints is retroactively applied, that is the Authority may receive complaints from before, on, or after 1 April 1989 (date of enactment) and there are no time limits. Sections 27 to 31 concern procedures on completion of investigation:

- Section 27 Procedure after investigation by Authority “[it] shall convey its opinion, with reasons, to the Commissioner, and may make such recommendations as it thinks fit, including a recommendation that disciplinary or criminal proceedings be considered or instituted against any Police employee.”

- Section 28 Procedure after investigation by Police.

After considering the Commissioner’s report and forming its opinion, the Authority—

(a) shall indicate to the Commissioner whether or not it agrees with the Commissioner’s decision or proposed deci sion in respect of the complaint;

(b) may, where it disagrees with the Commissioner’s decision or proposed decision, make such recommendations, supported by reasons, as it thinks fit, including a recommendation that disciplinary or criminal proceedings be considered or instituted against any Police employee.

- Section 29 Implementation of recommendations of Authority, the Commissioner is required to notify the Authority of the action (if any) proposed to be taken to give effect to the recommendation; and (b) give reasons for any proposal to depart from, or not to implement, any such recommendation, as soon as reasonably practicable.

- Section 30 concerns parties to be informed of progress and result of investigation in a timely manner where appropriate.

16. The New Zealand police also facilitate the public’s giving of positive feedback as well as expressing dissatisfaction or making complaints. The New Zealand police also contract out surveys to determine people’s perceptions of their service and how satisfied they are with the police, reports have been completed annually and published online since 2009.

17. In the US state of New York, a different type of oversight model is used, the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) made up of 15 members of the public, with public employees to conduct investigations. The Board is established under the New York City Charter Chapter 18-A Civilian Complaint Review Board and Section 440 (b) provides that the Board include:

- five members, one from each of the five boroughs, appointed by the city council;

- one member appointed by the public advocate;

- three members with experience as law enforcement professionals designated by the police commissioner and appointed by the mayor;

- five members appointed by the mayor; and

- one member appointed jointly by the mayor and the speaker of the council to serve as chair of the board.

None of the members shall hold any other public office or employment and no members shall have experience as law enforcement professionals, except for the members designated by the police commissioner [Section 440 (b) (2)]. The CCRB has the power to make its own administrative rules to fulfil its function (Section) and it has data transparency policy which presents descriptive data on CCB’s work:

- complaints received (arranged by use of force, abuse of authority, discourtesy or offensive language, by borough, by location, with or without video);

- allegations (arranged by type, outcome of investigation of allegation);

- victims/alleged victims (arranged by race/ethnicity, gender, age and outcome); and

- NYPD officers (arranged by how many have ever received a complaint, complaints according to one substantiated allegation, gender of officer, ethnicity of officer and education level of officer).

18. Several jurisdictions (Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, Singapore, the UK, the US, full list here) now use police body cameras as a transparency measure for a variety of reasons, including “deterrence theory – the presence of cameras deters police from behaviours they might otherwise have engaged in because the cameras involve the risk of censure and sanction”9. The UK police use body cameras and several pieces of legislation govern its use, such as the Data Protection Act 1998, Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996, Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 and the Surveillance Camera Code of Practice to name a few.10 The issues around regulating body camera use in police work is complex and outside the scope of this howtoregulate article but links for further reading are provided at the end.

VI. Police misconduct, discipline and immunity

19. Noting that an important police function is enforcement of the laws of the jurisdiction it serves, it would be contrary to justice if allegations of misconduct were not properly regulated. Police work can be dangerous and regulation should provide unambiguous defences or immunities for specific or limited circumstances. Disciplinary measures should serve as an effective deterrence and enforcement should meet community expectations because public trust goes down where perceptions of police impunity exist.

20. The police of Singapore are not exempted from the ordinary process of the law (Section 24 Police Force Act) but for acts done under the authority of a warrant police officer are not liable (Section 25 Police Force Act). Section 28 provides for the discipline of police officers:

- “A senior police officer may be interdicted, dismissed or otherwise disciplined by or under the authority of the Public Service Commission in accordance with the regulations governing disciplinary proceedings against officers in the public service” the Schedule of the Public Service Commission (Delegation of Disciplinary Functions) Directions Regulation lists complaints that constitute misconduct eg. personal violence to any person in custody; and

- Officers below the rank of inspector may be interdicted, dismissed or otherwise disciplined by or under the authority of the Police Force Act and its Regulations (G.N. No S 633/2004). The Regulations outline the procedures for discipline and punishment of substantiated complaints at Part III and the financial penalty (Section 31).

21. In Bolivia the Law on the Disciplinary Regime of the Bolivian Police (242NEC 4 de Abril de 2011) provides at Article 5 that:

- All police officers shall be accountable for the results arising from the performance of their functions, duties and powers, which may be administrative, executive, civil and criminal.

- The actions and facts that constitute possible offences are within the jurisdiction and competence of the ordinary justice system; without prejudice to disciplinary action when the facts also constitute a disciplinary offence.

The Bolivian Disciplinary Law also proscribes the penalties for serious offences:

- Article 13 [inter alia] physical assault on those arrested, detained or held in police cells constitutes a serious offence to be sanctioned with temporary withdrawal from the institution with loss of seniority, without enjoyment of assets from one to two years, without prejudice to criminal action

- Article 14 [inter alia] execution of cruel or degrading inhuman treatment, acts of torture, violation of human rights; and failure to comply with the procedures established for the use of force constitutes serious misconduct to be punished with withdrawal or definitive discharge from the institution without the right to reincorporation, without prejudice to criminal action.

C. Conclusion

The jurisdictions reviewed for this howtoregulate article about regulating the police contain several elements of best practice regulation and some jurisdictions such as New Zealand have very good police regulation as a result of a thoughtful regulatory reform process. Regulating the police can be a sensitive political issue, which has caused several jurisdictions to create reactionary regulation that has in many cases made law enforcement less effective. Generally, good regulation is borne from a consultative and cooperative process involving the regulated subject and the regulated object. However, police regulation has tended to be an adversarial process between the police, the public and the government of the day. This reflects the tension that police encounters on the ground and the diverging interests to be protected:

- The interest of the victims of criminals to obtain protection;

- The interest of the Community in prevention of unlawful behaviour in general;

- The interest of citizens not to be subject to unfair, violent and diminishing behaviour by police, even when being suspect of having infringed the law; and

- The interest in protecting the police agents as well, given that they merit, too, protection in so far as they are exposed to extreme risks.

Given the complexity of human interactions “in the field”, it is clear that regulation alone, without additional training on psychology and social aspects will fall short of a fine-tuned, balanced steering amongst these interests. However, regulation sets the frame and the tone. It cannot be underestimated in that role.

This article was written by Valerie Thomas, on behalf of the Regulatory Institute, Brussels and Lisbon, with the jurisdiction research assistance of Sharmely Zavala, Shin Won Kim and Eliza Foreman.

Links

The International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) is the world’s largest and most influential professional association for police leaders. https://www.theiacp.org/about-iacp

https://www.theiacp.org/resources/document/smaller-agency-best-practices-guides

Police Executive Research Forum https://www.policeforum.org/about-us

US based NACOLE https://www.nacole.org/qualification_standards_for_oversight_agencies

African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum http://apcof.org

Body cameras: UK, Canada, Australian state of Victoria and the Singapore Police Force Act recognises the use of body cameras at Section 2.

2 This research paper by Dr John Varghese provides a useful summary of different policing models in 7 jurisdictions: Police Structure: A Comparative Study of Policing Models https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228242038_Police_Structure_A_Comparative_Study_of_Policing_Models.

3 Table taken from Jenny Coquilhat’s report Community Policing: An International Literature Review page 20, https://www.police.govt.nz/sites/default/files/publications/community-policing-literature-review-2008.pdf.

4 Curriculum for the Central Police Academy https://www.cpa.go.kr/cpa2016/newly_police/sub1.asp.

5 Victoria Police entry requirements https://www.police.vic.gov.au/police-entry-requirements.

6 Police – frequently asked questions https://www.police.vic.gov.au/police-faqs#pay-leave-benefits-and-conditions-of-work.

7 US Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, “National Sources of Law Enforcement Employment Data”, April 2016 NCJ 249681, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/nsleed.pdf.

8 Oversight mechanisms of Sierra Leone’s Independent Police Complaints Board https://apcof.org/country-data/ierra-leone/.

9 Bradford, B. and Jackson, J., “Enabling and Constraining Police Power: On the Moral Regulation of Policing” LSE Law, Society and Economy Working Papers 23/2015, p. 10, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/35437915.pdf.

10 College of Policing, “Body-Worn Video”, UK Police Authorised Professional Practice, 2014, p. 7, https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/media/document/body-worn-video-guidance-2014_collegeofpolicing-uk.pdf.